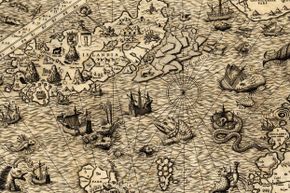

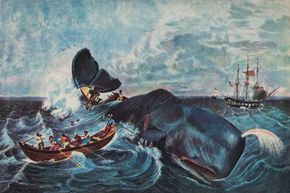

Once upon a time, we feared whales. Medieval maps of the world featured nightmarish sea beasts haunting the periphery of the known world, ready to devour adventurous sailors. But those gargantuan cetaceans have undergone a complete change of image, and nowadays we pay good money to go on boat tours for glimpses of creatures we often describe as "majestic."

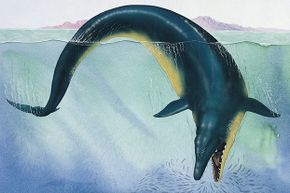

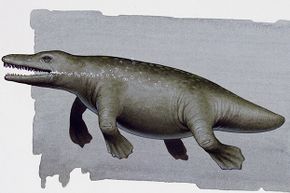

Maybe those ancient cartographers were tapping into some ancestral memory. If you were to go back far enough — way back to the Eocene epoch some 40 to 50 million years ago — you would see some terrifying proto-whales lurking in the tidewaters. While it's fairly common knowledge that our early ancestors slithered out of the ocean, what's less well known is that some of them weren't impressed. These creatures took a look, said "meh," and headed back into the big blue. Mind you, that turnaround took millions of years of adaptation. The point is, a few of those refuseniks were the great-grannies and granddads of modern cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises), and some of them bear a curious resemblance to medieval sea creatures. Here be monsters!

Advertisement