Great whites are the flashy man-eaters of the silver screen. Tiger sharks have a cool nickname. Among the three species of shark that are known to most commonly attack humans, the bull shark gets the least amount of press. What you may not know is the bull shark could actually be the most dangerous of them all. Why? Because it swims where humans do -- close to shore.

Advertisement

The bull shark goes by many different names. Its scientific designation is Carcharhinus leucas. Depending on where you are in the world, you might also hear it referred to as a Ganges shark, Zambezi shark, ground shark, shovelnose, freshwater whaler, swan river whaler or slipway grey.

By any name, bull sharks can be found in warm waters all over the world. They've been spotted as far north in the Atlantic as coastal Massachusetts and as far south as Brazil. In the Indian Ocean, you can find them from Africa and India to Vietnam and Australia. They tend to avoid the cold waters of the Pacific, though they have been seen from Baja, Calif., down to Ecuador.

What's interesting about the bull shark is that it's not just found in the ocean. It's one of only two species of shark that can live in freshwater -- the other is the rare river shark. Bulls are commonly seen in rivers and lakes, and not just in tidal creeks -- these guys really get around. They've been reported 2,200 miles (3,700 km) upstream the Amazon River and as far up the Mississippi River as Illinois.

The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) places the bull shark third on the list of unprovoked attacks on humans, with 77 incidences and 25 fatalities as of April 2008. The tiger shark comes in at second with 88 attacks, but both of these totals are dwarfed by the great white, which clocks in at 237 unprovoked attacks [source: ISAF]. However, shark experts believe that many bull shark attacks may go unreported in the waters of the Third World countries it often navigates.

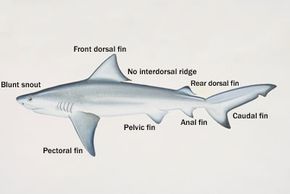

In this article, we'll teach you all you ever wanted to know about bull sharks. What they look like, what they eat, where they eat, how they reproduce and how they're able to survive in freshwater -- not to mention what makes them so deadly.