When it comes to accidental insect consumption, any 12-year-old boy can set you straight: The black dots in bananas are tarantula eggs, three centipedes crawl into your mouth every night while you sleep, and, of course, fig bars are full of baby wasps.

A simple internet search easily puts two of these grade-school urban legends to rest. However, an inquiry into the world of figs turns up stories that many people might find more than a little troubling: stories of fig plants teeming with insects and fruit having been split open to reveal hoards of small wasps.

Advertisement

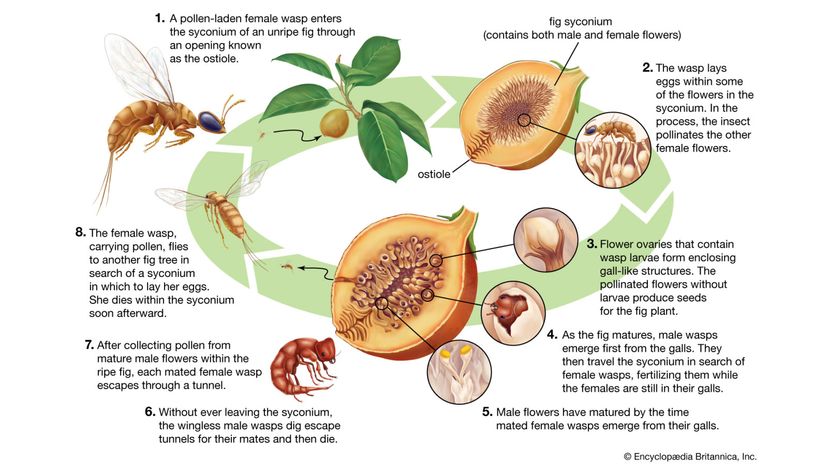

While these stories may not be all that appetizing, there's no reason to swear off figs quite yet. Those little insects are fig wasps, and they play an essential role in the fig's life cycle as the plant's only pollinator. That means that for pollen from one fig plant to reach another plant, fig wasps must do all the leg work. In return, the plant provides fig wasps with their only sources of food and shelter.

This arrangement is called mutualism. Both plant and wasp depend on the arrangement to survive, and without one, you wouldn't have the other.

But what happens when it's time to harvest the figs? Are the wasps still inside? Do the food companies scrape them out before they turn figs into jam? Or were the 12-year-olds right all along — are we really eating a mouthful of sweet baby wasp paste?