Mammoths, mastodons and saber-toothed cats weren't the only giants roaming ancient America. The Pleistocene was a geologic epoch that kicked off 2.6 million years ago. It lasted right up until Earth's most recent ice age ended, about 11,700 years before the present day.

When you live in a cold environment, being big has its advantages. Large animals tend to conserve body heat more easily than smaller ones. This is one of the major reasons why colossal mammals were so widespread during the frigid Pleistocene.

Advertisement

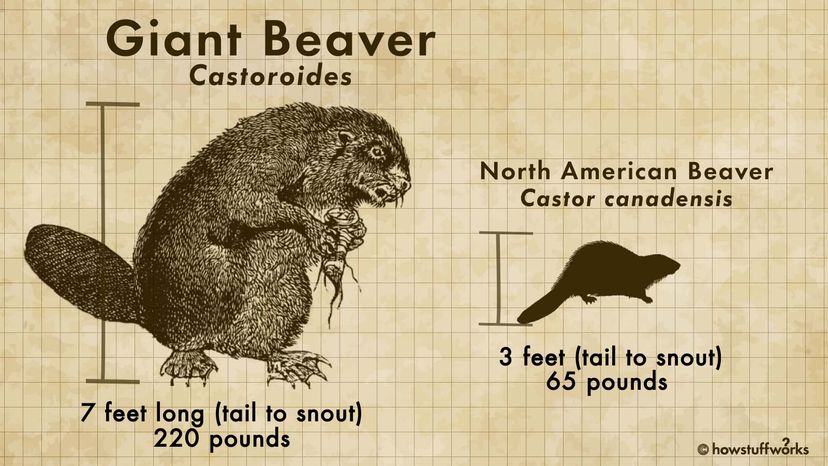

Castoroides was very much a product of its time. The largest rodent in Pleistocene North America, this big old beaver grew more than 7 feet (2.1 meters) long from tail to snout and could've weighed as much as 220 pounds (100 kilograms) or more.

Rivaling the American black bear in size, Castoroides utterly dwarfed the beavers that live today. Modern Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber) weigh just 29 to 77 pounds (13 to 35 kilograms) and the American species (Castor canadensis) has a similar body mass.

Proportionately, Castoroides had a narrower tail and shorter legs — albeit, with bigger hind feet — than its extant relatives. We also know that it didn't eat the same foods.

Woody plants are a crucial part of every living beaver's diet. The critters use chisel-like incisors ("front teeth") to gnaw through bark and take down trees. But even though Castoroides incisors grew to be a whopping 6 inches (15 centimeters) long, the teeth had duller edges by comparison.

Dental differences made it a lot harder for Castoroides to eat tree bark. And indeed, it looks like this wasn't really on the menu.

Using isotopic signatures in Castoroides teeth from Ohio and the Yukon, a 2019 study found that the giant beaver mostly ate softer aquatic plants. The findings say a lot about the rodent's ecological niche — and why it might've died out.

For starters, Castoroides probably didn't build dams. Not that there's anything unusual about that.

The earliest known beavers appeared during the Eocene epoch, which lasted between 55.8 and 33.9 million years ago. New evidence suggests the wood-harvesting specialists came along much later, perhaps around 20 million years ago. In all likelihood, these bark-fanciers used wood as a food source before any of them started constructing dams.

Since Castoroides fed on aquatic plants, its survival would've depended on wetland habitats. The animal was highly successful for a time: Castoroides fossils (representing at least two distinct species) have been documented in the Great Plains, the Great Lakes region, the American South, Alaska and numerous Canadian provinces.

Unfortunately for the mega-sized-beaver, North America became warmer and drier after the last ice age ended. Wetlands grew scarcer as a result.

Today's beavers use their logging skills to reshape the land around them so that it meets their own needs. With some well-placed wood in the nearest stream, a determined beaver can engineer brand-new ponds.

Yet if Castoroides didn't harvest wood or build dams, then it couldn't have followed suit. So theoretically, the decline in natural wetlands left the giant beaver more susceptible to extinction. The last of these creatures perished around 10,000 years ago.

Advertisement