Training Guide Dogs

Once it is grown-up, socialized and well-trained, the dog returns to the guide dog school for evaluation. Guide dog instructors look for a number of qualities, including:

- Intelligence

- Willingness to learn

- Ability to concentrate for extended periods of time

- Attention to touch and sound

- Good memory

- Excellent health

Even if a dog has all these qualities, however, it may be a poor candidate for training. Instructors screen out a lot of intelligent dogs because they have undesirable qualities, such as:

Advertisement

- Aggressive tendencies

- Nervous temperament

- Extreme reaction to cats or other dogs

After the instructor has spent some time with a dog, he or she decides whether the dog is a good candidate for guide dog training, not suited for guide dog training or not quite ready for guide dog training.

In some schools, if a dog is suited for training but not quite ready, it may go back to the puppy raiser for a month or so to mature. If a dog is simply not suited for training, the school will work to place the dog in another line of work, such as tracking, or find it a permanent home, usually offering it to the puppy raiser first. At Guiding Eyes for the Blind, only the top 50 percent of the returning puppies will stay with the school -- so the school places a little over 400 puppies with raisers each year, needing only 200 dogs for the training program. Of that 200, a small percentage will become breeding stock, for Guiding Eyes or another school, and the rest will be considered for the training program.

Training is a rigorous process for both the instructors and the dogs, but it's also a lot of fun. To make sure the dogs are up to the challenge, most schools test them extensively before beginning the training. The tests are designed to assess the dogs' self-confidence level, since only extremely confident dogs will be able to deal with the pressure of guiding instruction. If a dog passes the tests, it begins the training program right away.

Different schools have different programs, but typically, training will last four to five months. To make sure the dogs master all the complex guide skills, the instructors have to introduce them to each idea gradually. Once they have introduced what is expected of the dog, training is essentially a matter of rewarding correct performance and punishing incorrect performance. This works with dogs because they are pack animals and have a natural need to please an authority figure. The instructor, and later the handler, is simply stepping into the place of the alpha dog, the leader of the pack.

Unlike ordinary obedience training, guide dog training does not use food as a reward for good performance. This is because a guide dog must be able to work around food without being distracted by it. Instead, instructors use praise or other reward systems to encourage correct performance. The standard means of correction is pulling on the dog's leash, so that it pulls a training collar, giving the dog a slight pinch. Using this basic reward/punishment system, instructors work through the necessary skills for guiding.

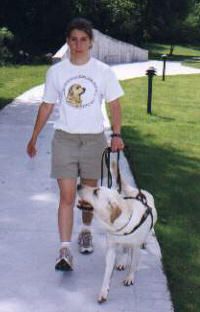

The first step is learning how to walk like a guide dog. This means walking in a straight line, without being distracted by surrounding activity. It also means keeping pace to the left and just ahead of the handler, and responding to leash corrections as well as verbal commands. Dogs learn how to walk correctly by degrees. First, they are simply taught to move directly from point to point. Then, the instructors steadily introduce greater and greater distractions, eventually venturing out into malls and city streets, and correct the dog if it veers off course. The process, which continues throughout the entire training program, is largely a matter of building up the dog's concentration level so that even the most tempting distraction won't lure it off course.

The dogs are also learning to stop at curbs from the very beginning. This is one of the most critical guide dog skills, because the safety of the handler depends on absolute mastery of the concept. Once the dogs have learned to always stop at a curb, they must learn how to judge potential dangers before crossing the street.

Many training schools have simulated street intersections on their campus so they can expose the dogs to a number of traffic situations. The dogs learn how to handle themselves safely around cars, and develop the ability to spot all sorts of potential dangers. This is the part of the training that focuses on selective disobedience. To become a guide dog, each candidate must demonstrate absolute mastery of crosswalk navigation.

One tricky part of training is teaching the dog to navigate obstacles with its handler in mind. Dogs learn fairly quickly to take the wide path around objects in the handler's path, so the handler won't trip over them. Learning how to deal with tight spaces is more difficult, but through reward and correction, the instructor gradually demonstrates to the dog that it should never go through a space that is too narrow or too low for its handler.

Additionally, dogs must learn a number of commands, must always stop for stairs and must practice all of the other necessary skills until they become second nature. This is a lot to learn, and not all dogs succeed in the program. At Guiding Eyes for the Blind, only about 72 percent of dogs that enter the training program make it to graduation.

The dogs that do master all of the skills by the end of the training period go on to the next step in the process: getting to know their handlers.