Nobody wants to be eaten by a wolf. It sucks. It's arguably the single thing that unites us all: humans, cows, raccoons, and rabbits alike. We're not keen on being dismembered and devoured.

We call the instinct that tells us to avoid becoming a wolf's lunch fear. And although nobody likes to feel afraid, the occasional roller-coaster ride aside, a recent study in Nature Communications shows that fear can actually be great for an ecosystem.

Advertisement

The thing that makes wolves — and lions and crocodiles and bears and killer whales — so terrifying is that they're apex predators: killing machines with no natural enemies. With the exception, of course, of us. An armed human is great at killing whatever it wants. And we often do.

"Three quarters of the world's top predator species are in decline. Lions, for examples, are down an order of magnitude in the past 50 years," says Dr. Liana Zanette, study coauthor and biology professor at Western University in Ontario, Canada. "And we've seen that this loss of large predators all over the globe is accompanied by some unforeseen ecological consequences."

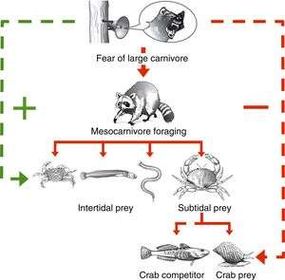

These consequences have a lot to do with balance in an ecosystem. When you remove the top predators from an ecological community, all the animals those predators used to eat experience a baby boom, but also start changing the habits that used to protect them from being eaten (e.g. nocturnal animals coming out to feed in the day, animals who used the woods for protection venturing farther afield, etc). This puts a lot of stress on the second-tier predator's prey, which might in turn create a population boom further down the food chain, which effects the next level down. And so on and so forth.

So what keeps a raccoon acting like a normal raccoon — eating at night, staying near the woods where it can easily scurry up a tree, looking around every few seconds while foraging for crabs for whatever might be stalking it? Fear. And Zanette's research team set out to experimentally prove what ecologists already anticipated: that it's not just through the act of consuming other animals that top predators influence the rest of the ecological community. The fear of that happening can be just as powerful.

Studying raccoons in British Columbia's Gulf Islands, where apex predators were killed off a century ago, the researchers first chose several islands to study, some with raccoons and some without. They matched them as closely as possible for habitat features, and measured the influence raccoons had on their prey base on islands where they were the top of the food chain.

"Where raccoons were present, the biodiversity of songbirds was less — they love songbird eggs and nestlings," says Zanette. "They also hammered crabs in the tidal flats, and polychete worms. Everything they like to eat, they ate."

The next step was to create a situation in which the raccoons were made to think there was a real chance they could be eaten by predators, to see whether the fear of being eaten would have the same ecological influence on the food chain as the actual presence of predators.

The research team set up an experiment on two different Gulf Islands over two years. On one island, they set up speakers that played the sound of barking dogs (which raccoons are afraid of), on the other, they set up speakers playing barking seals (which they're not afraid of). Think of similar broadcast systems on urban buildings that influence pigeon populations with predatory bird noises.

The team found that on the island where they broadcasted the recording of dogs, the raccoons actually ate 66 percent less, which led to an increase in the red rock crabs that the raccoons had been eating. And one step further, the boom in crabs meant a dip in the population of periwinkle snails the crabs ate.

So, fear — way more useful than we thought!

Advertisement