Of course, Franklin was not the only Founding Father with an interest in mastodons — or Big Bone Lick. As Virginia's governor, Jefferson became obsessed with the fossils of northern Kentucky. The mastodon bones helped him refute a widely-circulated argument about New World inferiority. In 1766, the French naturalist George Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon published his "Theory of American Degeneracy."

We contacted environmental historian Mark Barrow, Jr. He tells us via email, "Buffon was a materialist who believed that a limited number of life forms originally appeared on the earth through spontaneous generation and that as [they] migrated to different environments, they responded to the conditions they encountered there by changing form."

Buffon wondered why American creatures tended to look small and puny next to their Old World counterparts. (Next to an Indian tiger, the Mexican jaguar is a tabby.) His theory blamed the climate. Though he'd never set foot in the Western Hemisphere, he assumed that it was a cold, damp place.

"Buffon and some of his followers believed that the New World environmental conditions were such that they led the animals who lived there to degenerate," Barrow says. In the process, those creatures supposedly became "weaker, smaller, and less able to reproduce." And Buffon didn't stop there. To Jefferson's dismay, the naturalist claimed the same thing happened to human beings who'd moved to the Americas.

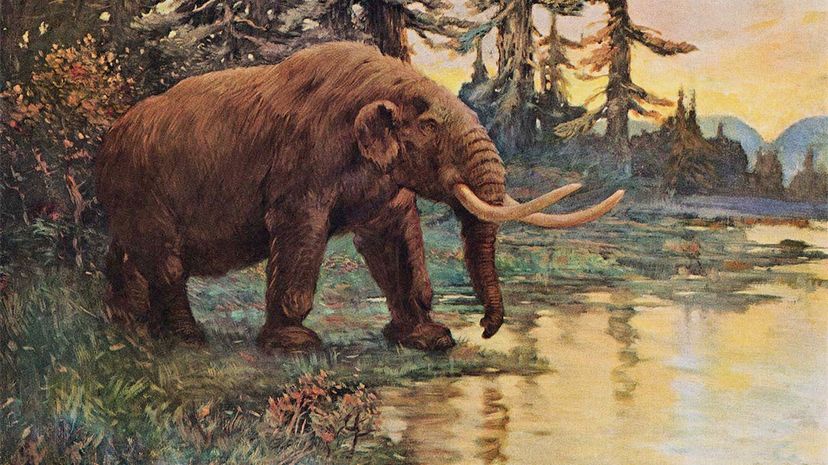

"Americans found this theory quite threatening, and Jefferson set out to disprove it," Barrow notes. Indeed, the Virginian spent a lot of time and energy trying to set the record straight. He aimed to show the world that, despite Buffon's claims, America had some animal giants of its own. To this end, Jefferson sent Buffon the massive corpse of an New World moose. In his 1780 book "Notes on the State of Virginia," he bolstered his case by writing about the giant mastodons of Big Bone Lick (and other American bonebeds). With the evidence mounting against it, Buffon's theory fell apart.