Yeah so having ravenous larvae invade your skin isn't much fun. Who knew, right?

Those botfly carriers (aka humans!) may feel what's been described as "intermittent stabbing pains" when the insects twist themselves around. That's because the freeloaders aggressively squirm as the host takes a shower or goes for a swim. One victim, a young girl, started hearing mysterious chewing noises after a botfly embedded itself by her ear.

By the way, human botflies aren't the only ones that can end up inside you. Equestrians who don't practice good hygiene around their animals can get infected by horse botflies. And sheep and reindeer botflies have also been known to cozy up inside unsuspecting people.

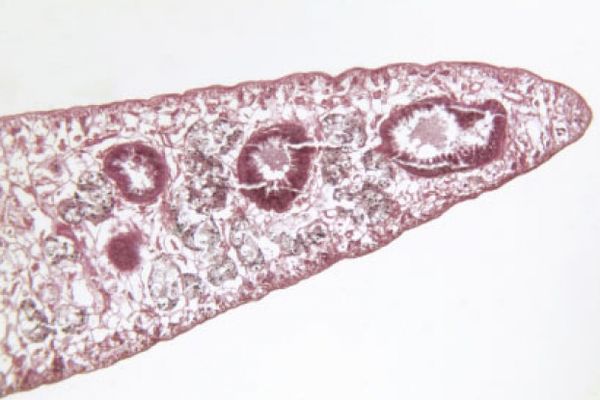

Should you find yourself toting botfly spawn around, don't go yanking them out on your own. The larvae are coated in sharp little spikes that help them get a grip on your tissues, and carelessly tugging on these parasites can break them apart, leading to infection.

Ideally, a trained physician will be able to extricate the pests with anesthesia and a scalpel. But if that's not an option, other methods are available. Some doctors use blunt instruments to squeeze down on either side of the botfly's hole until the pressure forces it out. Other than having to clean the wound daily, typically there are no other effects after the larvae are removed.

They might also try cutting off its air supply. Block the spiracles with a thick object and the larva should exit the host on its own accord. Weird as it sounds, pressing a slab of bacon or steak onto the wound will often get the job done. Who says red meat's bad for you?