Key Takeaways

- Toads do not cause warts; warts are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), not by contact with toads.

- The bumps on toads are glands that secrete toxins for defense, which resemble warts but are not infectious to humans.

- Handling toads may cause skin irritation from their secretions, but it won't lead to warts.

Australia has a big problem. Back in 1935, the government imported 101 giant cane toads (Bofo marinus) from Hawaii to Queensland to combat an infestation of cane beetles. Cane toads, which can weigh up to two pounds (0.9 kilograms), are indigenous to Central and South America [source: Florida Gardener]. Like most other non-native species introduced into an ecosystem manatees in Florida rivers and kudzu vines in the Southeastern United States are two examples), the cane toads soon began to wreak havoc, all the while shirking their original task -- eradicating cane beetles.

By 2008, the descendents of the original 101 cane toads brought to Australia numbered in the billions. What's more, they were on the move, leaving Queensland and encroaching upon cities in the Northern Territory, like Perth and eventually Sydney [source: Reuters, Peatling]. Billions of toads slowly moving toward civilization is unsettling enough; the bigger problem is the fact that cane toads are poisonous to many animals, including crocodiles, dingoes, some marsupials and myriad smaller animals.

Advertisement

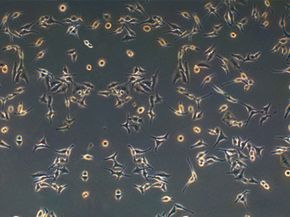

Because they're relatively new to Australia, cane toads don't have any natural predators as they do back in Hawaii. What's more, since they've only been on the continent for a relatively short time, other animals looking for a large, amphibious meal have yet to figure out that cane toads will kill them. It's the toxic cocktail of 14 chemicals that the toads secrete from their glands that poses such a danger. When the toad is threatened, these glands spring into action; the toxins are transferred from toad to the predator's mouth when it attempts to eat the toad. The chemicals work quickly and can cause nausea, paralysis and death.

Biologists and geneticists in Australia are studying the cane toad's life cycle in an effort to remove the development of a gene that allows them to reproduce [source: National Geographic]. Eventually the billions of toads will die out and the cane toad will become a bad memory in Australia. Despite the threat the cane toad poses to Australia's environment, the Aussies can rest easy that they won't also cause an outbreak of warts.

That's because the cane toad (or any toad, for that matter) isn't capable of producing warts.

Advertisement