"De-extinction" is a funny word, but it's one that might be used more and more in the coming decades. The sort of project made to look like far-fetched sci-fi in "Jurassic Park" is happening right now in Australia. Only it's not T-Rex that's being yanked out of extinction, it's the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf.

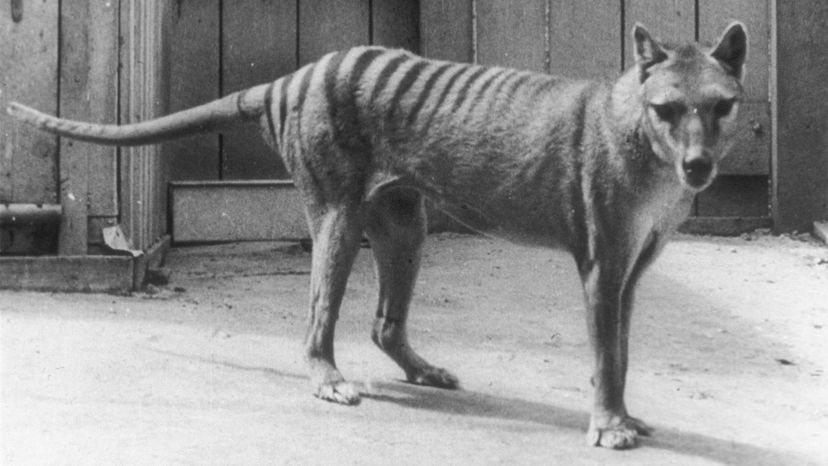

The last confirmed thylacine – his given name was Benjamin – died in an Australian zoo in 1936, the last wild thylacine having been killed seven years earlier. Thylacines were marsupial (Australia's speciality) apex predators, resembling a striped dog with giant jaws that could open 90 degrees. Before their demise in the 19th century, the Tasmanian tiger had been having a pretty rough couple of thousand years on Earth. Human population growth and climate change probably forced it out of its native range on mainland Australia around 3,000 years ago, although a popular hypothesis has been that the rise in dingo populations made it harder for thylacines to make a living in their ecological niche.

Advertisement

By the 1930s, the only wild thylacines lived on the island of Tasmania, where they were tenaciously picked off by sheep farmers once Europeans showed up in the 18th century. Benjamin was the last live thylacine anyone ever saw for sure, though hundreds of unconfirmed sightings have been called into government offices in both Australia and Tasmania since their extinction. Maybe it's wishful thinking – people just want the thylacine back, and we can't accept that it might just be gone for good. Now one group at the University of Melbourne – Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR) Lab – is working to "de-extinct" the thylacine through scientific methods.

In order to bring back the Tasmanian tiger, some fancy genetic engineering is required, obviously. Unlike the fictional "Jurassic Park" scenario, no cloning would be used, but, rather, a process called "gene editing." This process would take the stem cells of a close relative of the thylacine – a small mouse-like marsupial called a dunnart – and combine it with thylacine cells to create an embryo, which would be implanted into a female marsupial of a species closer to the size of a thylacine, such as a quoll. When the baby is old enough to leave the quoll mother, scientists would raise it and release it into the wild.

The reason the thylacine is a prime candidate for de-extinction is that its habitat remains mostly unchanged since its extinction – which is not the case for most extinct animals, since habitat loss is often the cause of extinction in the first place.

"While our ultimate goal is to bring back the thylacine, we will immediately apply our advances to conservation science, particularly our work with stem cells, gene editing and surrogacy, to assist with breeding programs to prevent other marsupials from suffering the same fate as the Tassie tiger," said Andrew Pask, the lead researcher on the TIGRR project, in a press release.

Advertisement