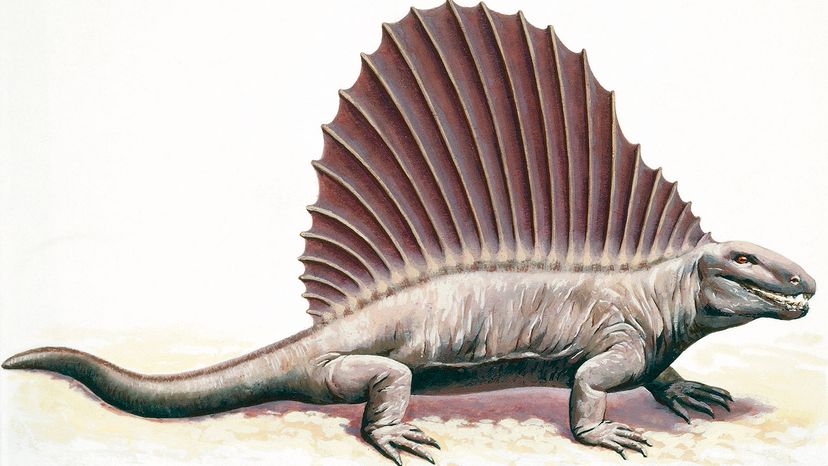

"Dimetrodon is what we call a 'synapsid,'" explains University of Chicago paleontologist Caroline Abbott in an email.

"About 310 million years ago, the first amniotes (vertebrates able to lay eggs on dry land) split into these two separate lineages, the synapsids and the reptiles, and the two groups have had separate evolutionary histories ever since," Abbott says. "Dimetrodon is one of the earlier synapsids."

Mammals are the only synapsids that are still around today.

The first true mammals wouldn't arise until sometime between 178 and 208 million years ago; long after Dimetrodon died out. Still, being a synapsid, the old fin-back had closer evolutionary ties to humans than it did to any modern reptiles — or to the dinosaurs, as we'll discuss later on.

How do we know the Dimetrodon was a synapsid? Well, there were a few clues that tipped fossil-hunters off after the creature was discovered in the 19th century.

"The key feature of all animals in the evolutionary lineage leading to mammals is the presence of a large opening behind the eye socket on the skull," says Hans Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in another email exchange.

"This feature becomes much larger in more advanced species and houses the jaw-closing muscles. You can feel those muscles if you put your fingers on your temples and clench your jaws," he adds.

Also, just like a lot of mammals, Dimetrodon was a heterodont. That means the creature's teeth didn't all look the same. On the contrary, its pearly whites came in a variety of shapes and held a variety of functions. According to Sues, Dimetrodon had "incisor-like front teeth, a large canine (eye tooth), and smaller teeth behind the canine."