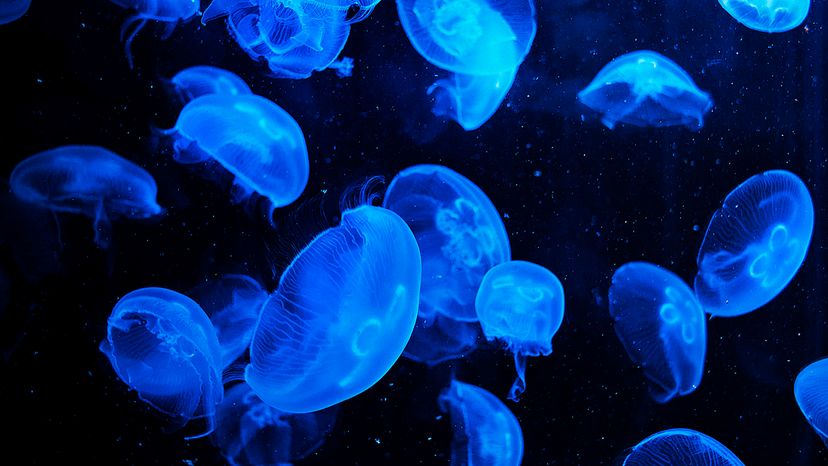

Moon jellyfish might look like ghostly saucers adrift in the blue, but they're more than just ocean ambiance. These translucent animals, known scientifically as Aurelia aurita, are part of a family of jellies that have lives perfectly tuned to drifting through the sea.

From their bell margin to their reproductive quirks, moon jellyfish are a species that’s both delicate and tough.

Advertisement

Unlike some of their jellyfish cousins, moon jellyfish lack long, potent stinging tentacles. That makes them relatively safe for humans, though their stinging cells can still irritate sensitive skin. They're commonly found near the coast, often found washed up on beaches in summer.