Squid are actually mollusks, although they look much different from their relatives the gastropods ( snails), and bivalves ( clams). Unlike other mollusks, which have a hard outer shell, squid have a soft outer body and an inner shell. Squid are part of the class Cephalopoda (meaning "head-footed"), a group that also includes the octopus, cuttlefish and nautilus. Cephalopods are divided even further into the eight-armed octopods (octopuses) and the 10-armed decapods (cuttlefish and squid).

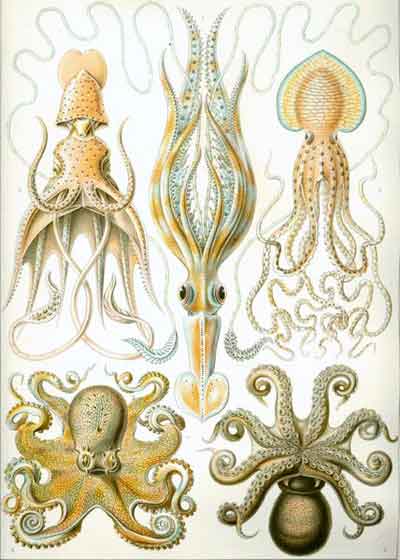

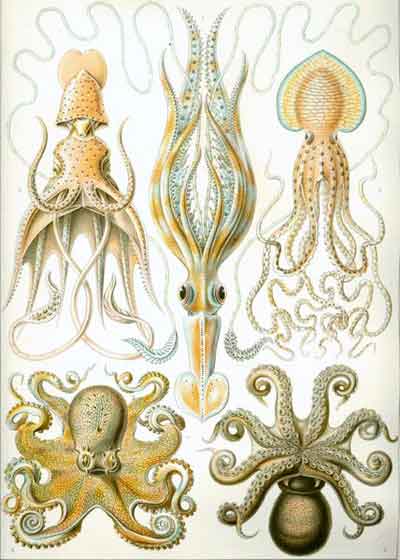

Public domain image

A variety of cephalopods in the subclass coleoida, which includes squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish, from Ernst Haeckel's "Art Forms of Nature"

Eating Squid

Several animals and birds like to feast on squid, including the sperm whale, the grey-headed albatross, tuna, marlin, shark, seals and penguins. Because several types of fish have such a predilection for squid, they make excellent bait.

Squid are also part of the human diet. We most commonly enjoy them breaded and deep frieÂd as calamari, or boiled and stewed as part of various seafood dishes. Although countries around the world eat squid, they are especially popular in regions bordering the Mediterranean Sea, as well as in Japan.

Image used under GNU Free Documentation License

Fried calamari

The squid emerged during a particularly bountiful stage in the ecological timeline -- 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period. So many different animal groups emerged during this period that scientists have termed it the "Cambrian explosion." Originally, thousands of species of cephalopods existed. Today, only four remain -- squid, cuttlefish, octopuses and nautiluses.

ÂThe earliest squid were most likely slow-moving creatures that lived in shallow waters. Squid today are versatile creatures -- they can make their homes in a variety of marine environments, from the deep sea to coastal surface waters.

Squid come in a wide variety of sizes and appearances. They can range from an inch to more than 65 feet in length. Most squid have a long, tube-shaped body with a small head. They have 10 arms (two of which are much longer than the others for grasping prey), which are lined with rows of suckers. Some varieties have claw-like hooks instead of, or in addition to, the suckers. In the center of the arms sits a mouth with a parrot-shaped beak that surrounds a sharp, bony tongue (called the radula). The squid's eyes are large and set into the sides of its head.

Squid are the most intelligent of the invertebrates (animals that lack a backbone), with a brain that is well-developed and larger in proportion to the animal's body than that of most fish and reptiles. They also have a sophisticated nervous system.

The squid's body is enclosed in a soft and muscular cavity called the mantle, which sits behind the head. As water flows through the mantle cavity, it passes over the gills and the squid absorbs oxygen to breathe. Beneath the head is a tube called the funnel. Wastes are excreted through the funnel, as is the squid's defensive ink.

We'll learn more about how squid use their funnels and the daily life of a squid in the next section.