Honeybee colonies are ingenious engines of productivity. An individual worker bee may take on seven different functions in her short six-week life, from wet nurse to wax producer to ventilator to far-flung forager [source: Alvéole]. And male drones, well, they get one shot at glory before being dragged out of the hive and sacrificed to the winter cold.

All in the name of honey, the golden energy source that will get the colony through the winter and keep the intricate, interconnected life cycle going.

Advertisement

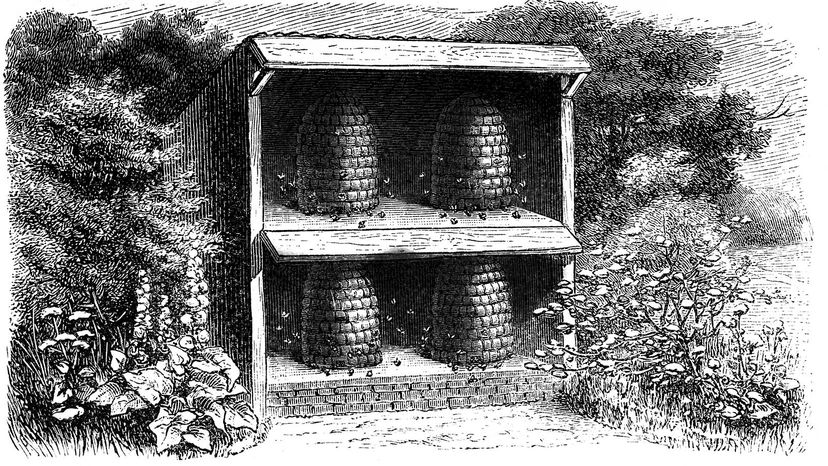

Beekeeping, when you get down to it, is the art and science of stealing honey from these hardworking bees without them knowing it. A beehive may be manmade, but the bees are very much wild animals doing what millions of years of evolution have taught them to do. The goal of the beekeeper is to keep the bees happy and healthy enough to do all the work while he collects the sweet, sweet profits.

Why Keep Bees?

Beekeeping is booming. In the United States alone, there were 2.67 million honeybee colonies as of 2017 [source: statista]. There are countless numbers of backyard beekeepers who have caught the "bug" and turned a pastime that was once reserved for hermit monks and rural farmers into a trendy hobby for suburbanites and urban lifehackers.

The attraction of beekeeping is obvious. Beyond the initial investment in some hive boxes, basic beekeeping equipment and bees, it doesn't require a lot of time, maybe 30 minutes a week plus two annual harvests. Then there's the daredevilish allure of playing with stinging insects, always good fodder for cocktail party conversation. And at the end of the day (or year), you get honey. Jars and jars of it. And who doesn't love honey?

But beekeeping – like growing your own organic vegetables or training a dog or raising children – is also harder than it looks. The weather is unpredictable, raining too much when the flowers are blooming, or not enough. Honeybees are susceptible to any number of pests and diseases, which you must learn to screen for and treat. If your hive is really healthy, it might swarm and you'll lose your best queen. Plus, bees sting. A lot.

Find a Mentor

Which is why our first tip about beekeeping is not to go it alone. Find yourself a beekeeping mentor. Most cities, towns and counties have a local beekeeping society. Join it. Go out with seasoned beekeepers and see their hives. Try to absorb their mountains of advice and then invite them over to help you load your first package of bees into the hive. And again, when you're not sure if your brood frames look right. And again, when you think you've spotted a queen cell, but you're not sure.

With a little luck and a lot of help, anyone can be a beekeeper. And there's nothing quite as satisfying as holding up that first dark amber jar of sweetness to the light, feeling its weight and thinking, "My bees made this for me" (though they really didn't and it's highly doubtful they're even aware of your existence).

Whether bees are actually aware of it or not, humans have enjoyed a unique agricultural relationship with them for millennia. Let's start with a trip back in time to meet the very first beekeepers.

Advertisement