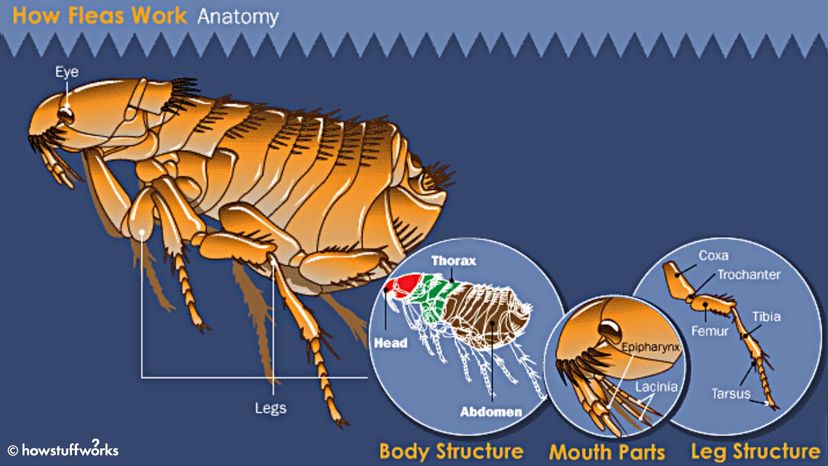

Flea Anatomy

Fleas are minuscule, but anyone who has seen one usually can recognize it with ease. They're tiny, flat, wingless insects that have a knack for jumping away before you can catch them. Their bodies are covered with hard plates called sclerites. So, if you do catch one, squashing it can be a challenge. Their hard, outer shell protects them from everything from an animal's teeth to hitting the floor after a long jump.

To the naked eye, a flea's exoskeleton seems completely smooth, but it's really covered in tiny hairs that point away from the flea's head. Their flattened bodies and these backward-pointing hairs are what enables them to crawl through a host's fur, and if something tries to dislodge them, the hairs act like tiny Velcro anchors. That's why a fine-toothed comb removes fleas better than a brush. The teeth of the comb are too close together for fleas to slip through, so it can pull them from the host's hair, regardless of which way a flea's hairs are pointing.

Advertisement

A flea also has spines around its head and mouth, with the number and shape varying according to the species. The mouth itself is adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood. Several mouthparts unite to form a needlelike drinking tube. Here's a rundown:

- Labrum and labium make up the "upper" and "lower" lips

- Labial palps are long, five-segmented sensory organs that come from the labium.

- Maxillae is a pair of short, wide plates located in front the labial palps.

- Maxillary palps: A long, four-segmented palpus comes off each maxilla.

- Fascicle are three long, slender stylets that are supported within the labial palps.

- Maxillary lacinae: These are the two outer stylets of the fascicle. They're serrated and blade-like.

- Median epipharynx: This is the central stylet of the fascicle that joins with the maxillae to form a tube-like food canal.

Fleas use their sharp maxillary laciniae to easily puncture the skin of their host. Then blood travels from their host through the tip of the median epipharynx up the flea's food canal. This requires a lot of suction, which comes from pumps in the flea's mouth and gut.

A flea's legs are adapted for jumping. As with all insects, a flea has three pairs of legs that attach to its thorax. The back legs are very long, and the flea can bend them at several joints. The process of jumping mimics the action of a crossbow. The flea bends its leg, and a pad of elastic protein called resilin stores energy just like a bowstring.

A tendon holds the bent leg in place. When the flea releases this tendon, the leg straightens almost instantly, and the flea accelerates like an arrow from a crossbow. This anatomy gives fleas the ability to jump about 7 inches (17.8 centimeters) vertically or 13 inches (33 centimeters) horizontally. In human proportions, that's a 250-foot (76-meter) vertical jump or a 450-foot (137-meter) horizontal jump. As it lands, the flea uses tiny claws on the ends of its legs to grasp the surface underneath.

Aside from these adaptations, fleas look a lot like most other insects, and their reproductive cycles are similar as well.