You wake up inside a hexagonal chamber. There's a burning hole in your side, and no matter how hard you try, you can't move a finger. Paralyzed, you watch in horror as the pale, bulbous creature at the other end of the chamber begins to crawl toward you with hungry, snapping jaws …

Sure, you might be the unfortunate victim in the latest sci-fi horror flick, but more than likely -- on this planet, anyway -- you're one of the millions of spiders and insects locked away by wasps each year to feed their growing broods of larvae.

Advertisement

Insect Image Gallery

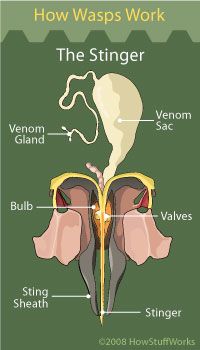

This parasitic nursery arrangement is rather common with most species of wasp. It's almost as infamous as the stings they pack to protect their nests -- both have helped to give wasps a somewhat vicious reputation.

Honeybees evolved away from their prehistoric wasp ancestors to pursue a quiet life of making honey to feed the family at home. Though most modern adult wasps' diets never evolved beyond eating pollen, they do bring home paralyzed victims for the kids to devour. Some even jumped at the opportunity to steal from bees and fellow wasps. Millions of years later, honeybees have achieved full-blown "cute" status and are the subjects of countless picture books, cartoons and children's toys. Wasps, on the other hand, are lucky to land a gig as a sports mascot.

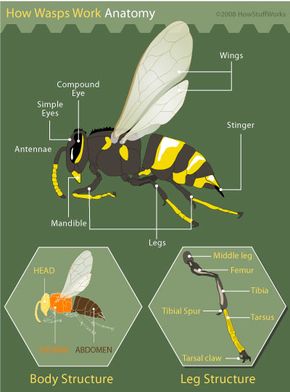

No matter how uncultured they may seem in comparison to bees, wasps lead complex lives. Despite the fact you'll never find anything called "wasp honey" at the local grocery store, wasps perform a vital service by helping to pollinate the world's plant life and eliminate various six- and eight-legged pests.

In this article, we'll examine the fascinating anatomy, lifestyle and social graces of one of the smallest creatures ever to chase grown and away from a picnic.