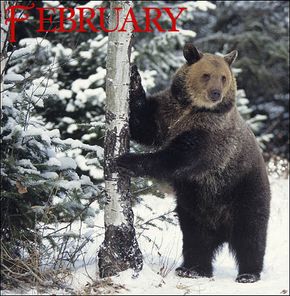

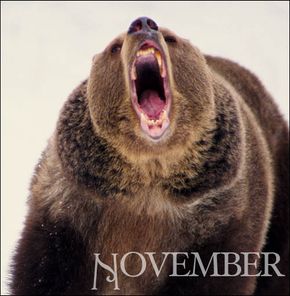

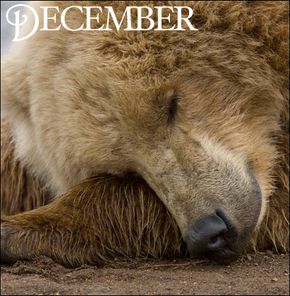

The time to retreat to the insular world of the den has arrived. Bears are not driven into dens because they can't handle the cold, harsh weather of winter. Rather, bears seek the sanctuary of dens because they cannot find enough food to survive during the winter. Instead of wandering the wasteland starving, bears take advantage of an amazing adaptation that allows them to conserve their energy and survive without food for the duration of the cold, dark winter months. In areas where the food source is abundant enough to survive, some bears actually practice a "walking hibernation," in which their metabolism slows but they continue to move about searching for food. For most bears, however, the den is the safest and most secure place to be once November rolls around.

Grizzlies generally excavate dens, with an entrance tunnel approximately 6-feet long but only 25-inches wide. This tunnel leads to a small chamber, 6-feet long, 5-feet wide and 3-feet high. These dens are dug into hill or mountain slopes.

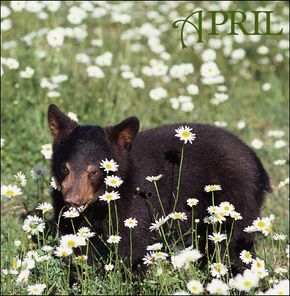

Black bears use a wider variety of sites for dens, including excavations, hollow trees, or even highway culverts and basements (the human inhabitants sometimes have no idea they have a black bear for a roommate!). Tree hollows provide the most insulated, secure dens, but logging practices have rendered them a rare option.

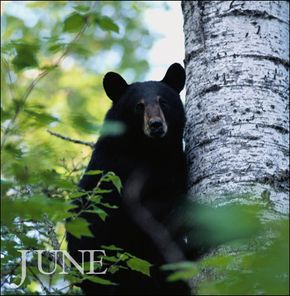

Once a satisfactory den has been located or excavated, the bears retreat and hunker down for the long winter ahead. Often, they enter the den during a snowstorm, possibly to hide their tracks and avoid being ambushed in such a vulnerable position. Once in the den, their metabolic rate slows by 50 percent. Their heart rate drops from 50 beats per minute to 10. Their body temperature falls by several degrees. The bears are now in a state of hibernation.

The hibernation of a bear differs from that of ground squirrels or other small rodents. These smaller animals lower their body temperature to within a few degrees of freezing or even slightly below the freezing point. They shiver violently every two weeks to raise their body temperature and awaken themselves long enough to urinate, defecate and eat a small snack. Bears are simply too large to successfully hibernate in this fashion — it would take too long to warm and cool their bodies to such extremes. Instead, they do not eat, drink, urinate or defecate. They burn more than 4,000 calories each day while in hibernation, but somehow they do not experience a significant loss in muscle mass or bone density. This remarkable adaptation allows bear to slumber deeply for months on end as winter rages beyond the entrance to their small, safe, warm haven.