Of all the natural world's curiosities, cephalopods are some of the organisms that perplex humans the most. In some ways they're like us: they can use tools, solve puzzles, and they have beautiful and complex systems for communicating with one another. But the hows and whys behind these behaviours are a little more cryptic.

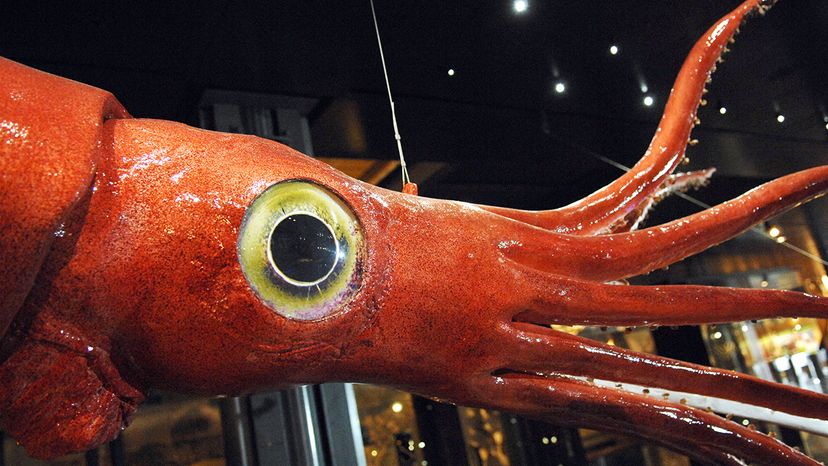

The giant squid (Architeuthis dux) is the second largest cephalopod in the world. The largest, for you curious folk, is the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni). Since giant squids live in extremely deep water environments, it's tough to study giant squid — the first images of a live animal were only captured in 2004, and most of what we know of them we have learned from bodies washed ashore. The largest giant squid specimen ever found measured 59 feet long (20 meters) and it weighed almost a ton.

Advertisement

What else about giant squids is, well, giant? Take a look at their eyes. They're the size of basketballs! Previous research suggests the reason for the humongous googly eyes a giant squid sports is that their sizes help the massive cephalopods see clouds of bioluminescence stirred up by their archenemy, the sperm whale, even at long distances through the inky deep sea waters. But intact giant squid specimens are pretty hard to come by, so researchers have never had the opportunity to investigate exactly how they process visual information. Until now, that is.

A team of researchers has published a paper detailing that the eyeballs of the giant squid work with the optic lobes in the animals' brains in a way scientists didn't quite expect. After a giant squid was caught by fishermen trawling off the coast of Taiwan, a team of Taiwanese researchers was able to create an MRI scan of the animal's optic lobe while it was still in good shape. Their findings, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, show that although these gigantic cephalopods have the largest eyes of any animal, the optic center of their brain is neither exceptionally large nor complex.

The research team found that the ratio between the size of the giant squid's eye and the part of the brain where visual information is processed is much smaller than those of other cephalopod species living in warmer, shallower waters. The giant squid's medulla, the part of the brain that merges visual information with motor tasks, was also unexpectedly small — suggesting that giant squid don't have the same kind of virtuosic camouflage and body patterning behaviors as their shallow-water brethren.

This makes sense, of course: a giant squid spends a lot of time in the dark more than a mile under the waves — not the most visually stimulating place on the planet. An oval squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana) or a pharaoh cuttlefish (Sepia pharaonis), two species whose optic-lobe-to-eyeball ratio was calculated for the study's comparison, spend a lot more time seeing and being seen than their giant, deep sea cousin, who lives in near complete darkness. Some cephalopods are even able to change the shape of their eyes to perceive different colors.

As for the giant squid? It'll have to stick to inspiring terror in seafarers, an arena in which — unlike taking advantage of that optic lobe — it excels.

Advertisement