Tick Anatomy

Many people group ticks into the same category as fleas and mosquitoes -- insects that suck blood. However, ticks are really arachnids. Adult insects have three pairs of legs, and their bodies are made up of three segments: the head, the thorax and the abdomen. Arachnids, on the other hand, have four pairs of legs. Spiders are also arachnids, but ticks aren't spiders. Spiders' bodies have two segments, the cephalothorax and the abdomen, while ticks' bodies aren't segmented in any way.

A tick's body is small and relatively flat, so it's easy for it to attach itself to a host and eat its fill before the host notices. This is particularly true for immature ticks, which can be smaller than the period at the end of a sentence. Hungry adult ticks are often smaller than sesame seeds. Some ticks have also adapted to blend in to their hosts' bodies. One example is the Aponomma komodoense, which feeds only on komodo dragons and is almost indistinguishable from a komodo dragon's scale. Many ticks have to stay in place for a day or more to finish a meal, so the ability to go unnoticed is central to its survival.

Advertisement

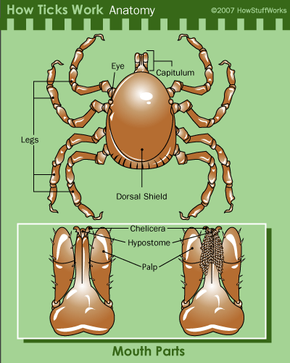

Adult ticks have eight legs, each of which is covered in short, spiny hairs and has a tiny claw at the end. These spines and claws have two main purposes. They help ticks grasp blades of grass, leaves, branches and other vegetation. They also allow ticks to grasp their hosts.

Ticks use their mouthparts to pierce their hosts' skin and extract blood. These mouthparts can vary from species to species, but in general, from the outside to the inside, a tick's mouth includes:

- Two palps, which move out of the way during feeding and don't pierce the host's skin

- Two chelicerae, which cut through the host's skin

- One barbed, needlelike hypostome

Hard and soft ticks both have these mouthparts, although you can only see them on a soft tick if you look at its underside.

The barbs on the hypostome are like the barbs on a fishhook. They point back toward the tick, making it difficult to remove the tick without damaging the skin. Some ticks secrete a cementlike substance with their saliva, which dissolves when the tick is ready to drop off of its host. This substance can make it even harder to remove the feeding tick. The saliva also keeps the host's blood from clotting while the tick eats. But unlike a flea's saliva, it doesn't usually include compounds that cause itching and swelling.

As a tick eats, its body, or idiosoma, expands, although the amount of expansion varies. The scutum of a male hard tick covers much of its back, so its body can't stretch to hold a lot of blood. Soft ticks don't have scutums to get in the way of feeding, but they don't require an immense store of blood to lay eggs, so they don't swell as much as hard ticks do. Female hard ticks swell immensely as they store the blood they need to lay their eggs.

Next, we'll look at ticks' life cycles in more detail, and we'll explore the differences in feeding patterns between hard and soft ticks.

At its most basic, a tick is a parasitic blood pump. Like all parasites, it feeds off of its host without giving the host anything in return. A tick's body has numerous adaptations that allow it to find hosts and ingest their blood.