When is it an OK time to panic? After 2016 has handed us the hottest year on record, Zika virus, Syria, Brexit, the deaths of a handful of beloved cultural figures, police shootings, church burnings, and the most acrimonious presidential election season in U.S. history, it seems we've finally gotten to a place where it's appropriate to freak all the way out.

Because science has found another two-headed shark.

Advertisement

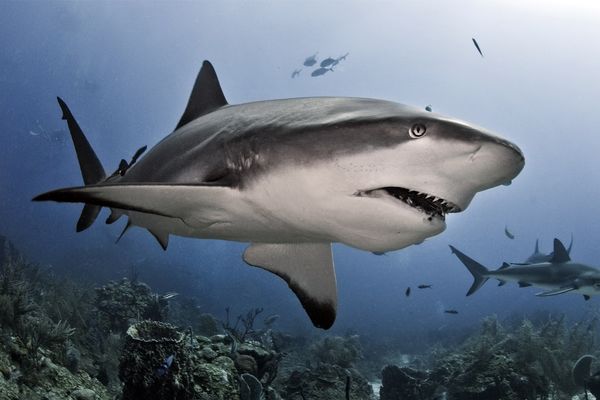

OK, so it's actually a shark embryo. But still. A recent paper in the Journal of Fish Biology describes a dicephalic (the fancy scientific word for "two-headed") sawtail catshark (Galeus atlanticus) embryo discovered in a lab where catshark eggs were being grown for cardiovascular human health research. But this oddity isn't the first scientists have found in recently. In 2013, a two-headed fetal bull shark was found inside a female captured off the Florida Keys. Others were reported from the Pacific off the coast of Mexico in 2011, and another conjoined bull shark fetus was found by a fisherman in the Indian Ocean in 2008.

What could possibly be the meaning of all this shark double-headedness?

First of all, nobody's sure how common this mutation is in nature, because although two-headedness can be attributed to the conjoining of twin fetuses or the duplication of a face on just one body, these types of mutations don't make for super robust individuals. So, the reason you don't see a lot of dicephalic adult sharks swimming around like something out of "The Hunger Games" is that they probably die young, or before they're even born.

The difference between the most recent dicephalic catshark and the "double monsters" found in the past, besides being grown in a lab rather than in the ocean, is that it came from an oviparous, or egg-laying, species, rather than an ovoviviparous species whose eggs hatch inside the mother. The researchers are pretty confident the lab-grown catshark eggs hadn't been exposed to any radiation, chemicals or infections that might cause a genetic mutation, so it's most likely that the two-headed fetuses are a result of a spontaneous genetic defect. But in wild sharks, the genetic mutations might come from the outside: water pollution, inbreeding brought on by shrinking populations, infections and diseases.

Either way, one thing we don't have to worry about are giant two-headed shark attacks, in addition to everything else 2016 is laying on us.

Advertisement