When you fill your dog's bowl with kibble, does Fido ever squirt ketchup on top before digging in? Or maybe your cat adds a dollop of tartar sauce to its fish-flavored mash prior to consumption?

No? Not surprising. Seasoning one's food seems like a uniquely human trait. We've been sprinkling salt to flavor our meals as far back as 10,000 B.C. [source: UK Food Standards Agency]. Roman soldiers received part of their compensation in the form of salt, hence the word "salary." Today, you'd be hard-pressed to find a house without a decently stocked spice rack.

Advertisement

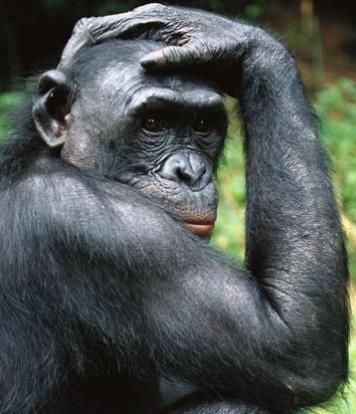

However, a group of Japanese monkeys, or macaques, challenged that notion during an experiment in the 1950s. As you've probably guessed, Japanese monkeys inhabit all islands of Japan, except for Hokkaido. This geographic range includes subtropical to subarctic climates, making macaques the northernmost-dwelling, nonhuman primates in the world [source: Gron]. To prepare them for such chilly conditions, Japanese monkeys are outfitted with thick brown or gray fur and resemble pink-faced Ewoks.

Groups of around 30 to 40 macaques live together in male-dominated units called troops. They shift between hanging out in trees and on the ground, although females prefer to spend more time aloft [source: Gron]. After reaching sexual maturity, males will leave their own families to travel among different troops in order to mate [source: Tanhehco].

When it comes to food, just about anything goes for macaques. Researchers have documented that the monkeys munch on more than 213 types of plants, not to mention insects and dirt [source: Gron]. For this reason, Japanese monkeys are considered omnivorous animals. Testifying to their broad culinary tastes, captive macaques at Ohama Park in Osaka, Japan, have now been put on a strict diet. Years of devouring snacks from visitors, such as bread and candy, have added up. One particularly stout monkey weighs twice the average for the species, tipping the scales at 63 pounds (29 kilograms) [source: Ryall]. Park officials now request that people not feed the monkeys since they'll readily eat any treat thrown their way.

But what about seasoning their food? Do these indiscriminate eaters pay attention to flavor? Find out on the next page.

Advertisement