On Jan. 29, 1992, a cargo ship spilled a portion of its load into the Pacific Ocean, releasing thousands of little yellow rubber duckies to journey around the globe. Amazingly, many of them are still out there, no worse for the wear, bravely forging ahead. They've ridden ocean currents up the eastern coast of the United States, along the shores of Greenland and through pack ice in the Arctic Ocean [source: Bruxelles].

Advertisement

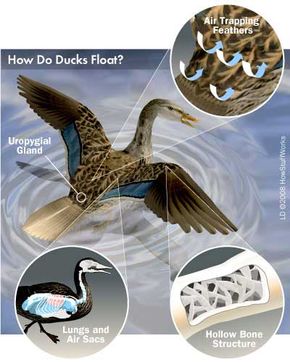

How these ubiquitous bathtub toys remained afloat for more than 15 years isn't much of a mystery. After all, they're made of rubber, filled with air and light as a feather: It's no wonder the denser seawater holds them up. But how do their flesh-and-blood brethren accomplish the same task? Real ducks aren't made of plastic, and they contain more than just air.

The concept is actually simple, but to understand it, you first have to understand why anything floats. Objects either float or sink in water because of something called buoyancy. When an object placed in water weighs less than the amount of water it displaces, it floats. If it weighs more, it sinks.

If that cargo ship had been transporting bowling balls, you can bet they wouldn't be cruising the high seas. Rubber duckies, however, which typically weigh no more than say 5 grams and take up about 75 cubic centimeters of space, are a different story. The 75 cubic centimeters of water they displace weighs about 75 grams (0.16 pounds), so that water significantly outweighs them. Obviously, the heavier seawater will keep them afloat.

Real ducks also are lighter than the water they displace, but it takes several things working in tandem to achieve that lightness. Learn why it's more complicated than rubber and air next.

Advertisement