World-famous "Crocodile Hunter" Steve Irwin, known for seeking out and handling some of the most dangerous animals in existence, died on Sept. 5, 2006, in a shocking accident with a stingray. Six weeks later, a stingray jumped into a fishing boat in Florida and stabbed 81-year-old James Bertakis in the chest.

Stingrays are considered by most experts to be docile creatures, only attacking in self-defense. Most stingray-related injuries to humans occur to the ankles and lower legs, when someone accidentally steps on a ray buried in the sand and the frightened fish flips up its dangerous tail. Officials called the Florida incident a totally freak occurrence. In the early stages of examining the Steve Irwin accident, some experts hypothesized that the combined positions of Irwin (above the fish) and his cameraman (in front of the fish) could have made the stingray feel trapped and triggered a defensive attack; others point out that completely unprovoked stingray attacks are not unheard of.

Advertisement

Stingray-related fatalities (in humans) are extremely rare, partly because a stingray's venom, while extraordinarily painful, isn't usually deadly, unless the initial strike is to the chest or abdominal area. In Irwin's case, the barb actually pierced his heart. James Bertakis was also stabbed in the chest, and possibly in the heart, but he did not attempt to remove it, which could prove to be part of the reason he survived the attack.

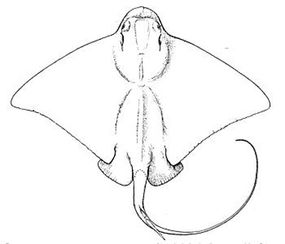

News agencies reported that Irwin's encounter was with an Australian bull ray, estimated to weigh about 220 pounds (100 kilograms). Irwin was snorkeling in about 6 feet (2 meters) of water, filming a new documentary titled "Ocean's Deadliest" off the coast of Australia. Irwin was swimming with one of the larger species of rays out there — Australian bull rays can be up to 4 feet (1.2 meters) wide and 8 feet (2.4 meters) long — but all stingrays use the same attack mechanism regardless of size. The mechanism is called a sting, up to 8 inches (20 cm) long in a bull ray, located near the base of the tail. The sting contains a sharp spine with serrated edges, or barbs, that face the body of the fish. There is a venom gland at the base of the spine and a membrane-like sheath that covers the entire sting mechanism.

When a stingray attacks, it needs to be facing its victim, because all it does is flip its long tail upward over its body so it strikes whatever is in front of it. The ray doesn't have direct control over the sting mechanism, only over the tail. In most cases, when the sting enters a person's body, the pressure causes the protective sheath to tear. When the sheath tears, the sharp, serrated edges of the spine sink in and venom flows into the wound.

A stingray's venom is not necessarily fatal, but it hurts a lot. It's composed of the enzymes 5-nucleotidase and phosphodiesterase and the neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin causes smooth muscle to severely contract, and it is this component that makes the venom so painful. The enzymes cause tissue and cell death. If the venom is introduced into an area like the ankle, it can usually be treated. Heat breaks down stingray venom and limits the amount of damage it can do. If not treated quickly enough, amputation might be necessary. But if the venom enters the abdomen or chest cavity, the resulting tissue death can be fatal because of the major organs located in the vicinity. If the spike enters the heart, as was reported to be the case in Steve Irwin's accident, the results are typically fatal.

While a stingray's venom can do serious damage, the most destructive part of the sting mechanism can actually be the barbs on the spine. The sharp tip of the sting enters a person pretty smoothly, but its exit is roughly equivalent to backing up over those "severe tire damage" blades. Remember that the points of the barbs are facing the stingray. Even if venom weren't involved at all, pulling the spike out of a human's chest or abdomen could be enough to cause death from the massive tearing of tissue that results.

Advertisement