Octopus Behavior

The octopus spends much of its solitary life in a den, leaving at night to hunt. For reasons not clearly understood, it generally likes to search for new real estate every week or two. Octopus dens are usually under a rock or in a crevice, and the animal has even been known to take up residence inside an old, discarded bottle on the sea floor.

When it does venture out of its den, the octopus uses one of several methods to get around. The preferred method of locomotion for many octopuses is a form of walking. Rows of suckers on the underside of each arm enable the octopus to move itself forward along the sea floor. Because its arms are highly sensitive – each sucker has up to 10,000 neurons – the octopus can also learn a lot about its surroundings this way, and it may even chance upon a tasty meal.

Advertisement

But the octopus can jet into much higher speeds if needed. When it wants to make a quick escape, it takes water in through its mantle and then closes it off to seal in the water. Next, it expels the trapped water forcefully through its funnel, which propels the octopus in the opposite direction at speeds of up to 25 mph (40 kph). Using this method, which is a lot like filling up a balloon with air and then letting it go, the octopus can change its direction by pointing its funnel a different way.

The rarer, more primitive and less researched finned octopus (cirratte) can also use its fins for swimming. It often combines the use of its fins with the propulsion method. Little is known about the cirrate, however, because it lives in very deep water. Most articles, like this one, deal with the more common, non-finned octopus (incirrate).

If an octopus isn't busy preventing itself from becoming a meal, odds are it's out looking to make a meal out of something else. The octopus uses a variety of techniques to capture and consume prey. Its long, flexible arms are ideal for reaching into crevices after tasty crabs and crawfish, and its soft bodies are able to squeeze into tiny spaces after small fish or clams.

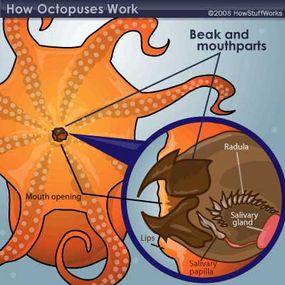

And although the octopus does not have any teeth in the standard sense, it has several other just as effective methods of cracking into crustaceans and mollusks. The octopus has a veritable Swiss Army knife of tools located inside its mouth to pry open the shells it can't open with its tentacles. Directly inside its mouth, it has a hard retractable beak similar to a parrot's. This beak is useful for breaking open clam shells and tearing apart flesh. Next to the beak is the radula, a barbed tongue the octopus uses to scrape an animal out of its shell once the shell is opened. And if these tools don't do the trick, it also has a tooth-covered organ called the salivary papilla that it can use to drill into shells. The papilla's bodily secretion also erodes the shell and then weakens the prey so it can be consumed.

One of the octopus's preferred methods for capturing prey while swimming is to envelop it in the web of skin between its tentacles, as though capturing it with a net. Then it devours the prey with its beak.

In spite of the effort it can take for an octopus to make a meal, most species grow and gain weight quickly. Next, we'll look at why this happens – and how adults manage to mate without all their legs getting in the way.