There are a lot of things about goblin sharks that scientists don't know. But one thing is undeniable -- goblin sharks are not attractive. Although you'd be hard-pressed to find a person who adores the visage of any shark, goblin sharks stand out as the ugly ducklings of the family.

The scientific name of the species is Mitsukurina owstoni, but its memorable mug earned the goblin shark its common name. Aside from its superficial traits, there is little else "goblin" about this fish. Unlike their more predatory cousins, goblin sharks pose little threat to humans and generally swim at levels too deep for human contact.

Advertisement

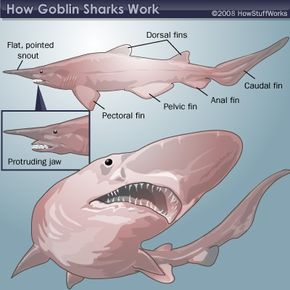

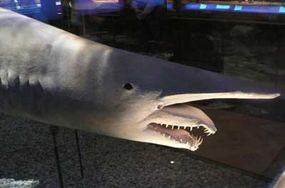

So what is it about goblin sharks that repels? Beady eyes, an enormously flat snout and retractable jaws design a bizarre face you might see in a Picasso painting. The elongated nose in particular creates a strange facial proportion as though the mouth forgot to catch up with it. Three rows of around 25 crooked needlelike teeth line the tops and bottoms of its gums [source: Florida Museum of Natural History]. Its jaws also sit strangely on its face because of a double set of ligaments that let goblin shark extend and retract them for feeding purposes.

The rest of a goblin shark's body is flabby with transparent pinkish skin from the blood vessels that shine through. Averaging around 12 feet (3.6 meters) long, goblin sharks are hefty creatures, weighing in at about 400 pounds (181 kilograms) [source: Florida Museum of Natural History]. They live along outer continental shelves and seamounts (mountains rising from the sea floor) rather than in open waters. But since the first recorded sighting in 1898, only 50 or so goblin sharks have been caught around Japan, Portugal, the Gulf of Mexico and the California coast.

Despite existing in modern scientific history for little more than a century, the goblin shark species has been around much longer. And it just may be its unpleasant face that brought it through multiple millennia.

Advertisement