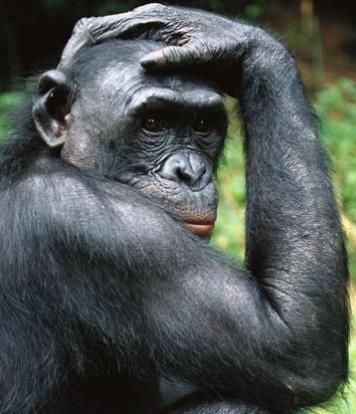

Think you have to go to a zoo to see monkeys in the U.S.? Well, think again. Florida, the unofficial national home of wildlife weirdness (alligator farms, the skunk ape), is also home to a colony of feral rhesus macaques, a species of Southeast Asian monkeys that have been living in Silver Springs State Park near Ocala since the 1930s.

So how did these non-native monkeys get there in the first place? They didn't escape after the filming of the 1939 movie "Tarzan Finds a Son!" as local legend has it. "The most plausible explanation ... is that a few individuals were released there in the 1930s by a tour boat operator who wanted to enhance the excitement value of his jungle boat cruises that he ran along the river," says Erin Riley, an associate professor of anthropology at San Diego State University, via email.

Advertisement

Riley's the author of a recent study of the primates. The monkey colony gave Riley, a primatologist, the perfect opportunity to study monkeys and their interactions with humans in the wild, without going too far from home.

"This population is important," she says, "because it further demonstrates the tremendous behavioral and ecological flexibility of the rhesus macaque. It also reveals the impact that human behavior can have on primate behavioral ecology and long-term survivability."

Riley and graduate student Tiffany Wade spent five months observing and counting the monkey population in Florida's Silver Springs State Park, an activity that put to rest some of the rumors about the population.

For example, anecdotal reports stated that thousands of monkeys lived in the park. Riley and Wade counted only 118. While that's not a huge number, they are wild animals and there are always concerns when wild animals and humans (sometimes pretty wild themselves) mix.

But, Riley and Wade found that the monkeys and humans seem to be getting along pretty well, thank you. The researchers found that 87.5 percent of the macaques' diet came from their habitat, while 12.5 percent came from humans. This means that the monkeys are mostly self-reliant and that the population persists not because of people feeding them.

Some of the monkeys' favorite human foods were grapes, peanuts and fleshy fruits like oranges. Riley approached some of the people who fed the primates to find out why they did it.

"Some boaters told us that feeding the monkeys could not possibly be harmful because there are no signs that tell them not to feed," she says. "Some park visitors expressed a level of concern about the monkeys' well-being, claiming 'they look hungry.''

This lack of signage could be a problem. Park officials, she notes, have resisted putting up signs or even talking about the monkeys, hoping to keep their existence quiet.

"The sense I've gotten is that [park officials] are concerned that if the monkeys are advertised, more people will come to the park to see the monkeys and potentially feed them or interact with them in other ways," says Riley, which could cause the monkeys to become aggressive or spread disease.

Riley believes that in this instance it's education, not ignorance, that's bliss. She'd like to see signs and programs "to educate people about the macaques' origin, how they have managed to persist in the area and how to best interact with them," she says.

And what about concerns that the park can't sustain these animals long-term? "Now that trapping [monkeys] has been banned, we can gain a better idea of the rate of population growth," she adds. "We also still need to know more about the number of individuals that exist beyond the Silver River and possible selective pressures (e.g., disease, predation) that might be limiting population size."

Advertisement