We all know that elephants mourn their dead, female lions are the primary hunters and giraffes. . . are tall? Seem friendly? All you need to do to assure yourself you don't know much about giraffes it to try explaining to a kid that a cow says moo, an owl hoots and a giraffe, um, probably makes a chewing sound when eating plants?

So most of us don't know that much about them — fair enough. But it turns out, even those who study giraffes for a living didn't know as much as they thought about the animal either. Only recently scientists discovered through genetic testing that there are four distinct giraffe species. It was a huge finding, considering they had assumed all giraffes were one and the same, with only subspecies differentiating them.

Advertisement

Now don't think giraffe biologists and zoologists were asleep on the job. This new discovery actually speaks to both how difficult it is to determine different species without significant morphological differences, along with the fact that giraffes have traditionally been sidelined for research on the more sensational lions, gorillas and elephants.

Stephanie Fennessy is a co-director of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (which was a partner in the research), and she says she has "no idea" why giraffes aren't studied like other animals. "That's why we call them the forgotten giants," Fennessy says. "They don't have the same attraction to researchers like other animals, maybe due to a lack of clear social structures."

According to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, giraffes have one of the least structured types of socialization among the animal kingdom. Although the females do bond, they don't seem to form the deep emotions of some animals that spend many years together. This lack of social structure may be an adaptive measure for survival in the wild.

The discovery of the subspecies was actually a bit accidental. The Giraffe Conservation Foundation initially teamed with a geneticist at Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre and Goethe University in Germany to learn about some of the differences in what were assumed to be giraffe subspecies, and use that information in conservation relocations.

What they found was that there were more significant differences than expected. In some cases, the genetic sequencing differences were as great as those between brown bears and polar bears, for instance. Expanding their research, they decided to take even more skin samples, including 190 giraffes across the range of (previous) subspecies. And no ladders necessary, Fennessy says. "We mainly use biopsy darts that drop out and take a sample," she explains. "We also got samples from dead animals and those we collared."

That genetic data concluded that there are actually four species of giraffe – and each only mated within their species. The new species are categorized as the northern, southern, reticulated and Masai giraffe. (The northern and southern giraffes include a few subspecies, as well.)

The nitty-gritty of the biological implications may be thrilling for zoologists and scientists, but you might be curious: Can we tell these four species apart? Actually, yes – here are a few of the physical differences.

The northern giraffe is made up of the Kordofan, Nubian, West African giraffes and Rothschild's giraffes. Their lower legs are usually white and not patterned.

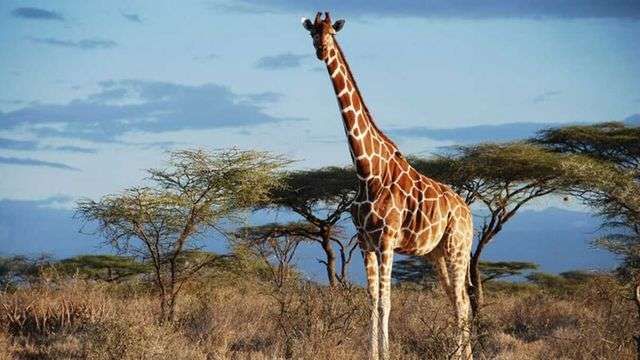

Reticulated giraffes usually have brown-orange patches clearly defined by a network of thick white lines even on their legs.

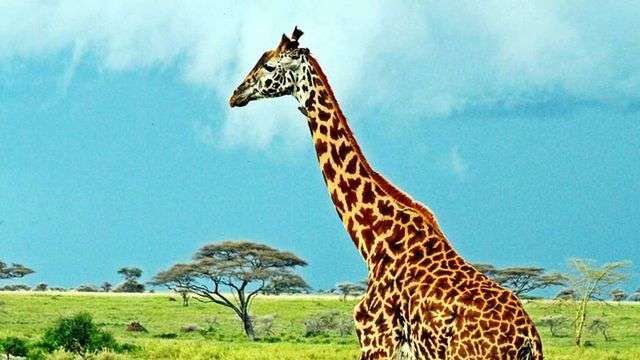

Masai giraffes tend to be darker than the other species with large, dark brown, distinctively vine leaf-shaped patches on their bodies and legs.

Southern giraffes include the Angolan and South African giraffes. They're relatively light in color and only have three ossicones (those cute little nubby horns) on their heads. Northern giraffes usually have five.

The new designations could be helpful for conservation purposes. While giraffes were defined as "least concern" for endangered status before, there is a push to list them as threatened since their numbers have dropped from 150,000 to less than 100,000 in the past three decades. And with four new species, each can be evaluated for endangered status and given more strategic conservation efforts.

Advertisement