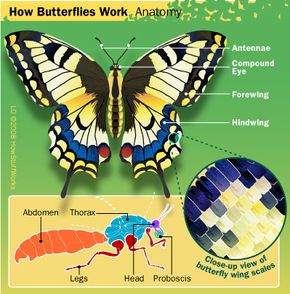

Butterflies' lives are all about flight. Their vibrant wings are the largest, most visible parts of their bodies, and they spend much of their time in the air. Flying takes a lot of energy, and to get this energy, butterflies drink the nectar from flowers, which require the power of flight to reach. Even when resting, butterflies are often preparing for flight by keeping their wing muscles warm enough to move.

All this flight isn't just for enjoyment, and butterflies' colorful wings aren't just for show -- it all ties to reproduction in one way or another. Butterflies use the colors on their wings for camouflage and as a warning to predators, which helps them stay alive long enough to reproduce. They also use wing shape and color to identify, and sometimes impress, a mate.

Advertisement

Finding a mate and reproducing are often the last events in a butterfly's life -- most live just long enough to start a new generation of butterflies. There are some species that live long enough to migrate thousands of miles or hibernate through the winter. But at the end of the journey or the start of spring, the butterflies' actions are still the same. They mate, the females lay eggs, and all the adults die. The eggs hatch into caterpillars, which eventually grow into similarly short-lived butterflies.

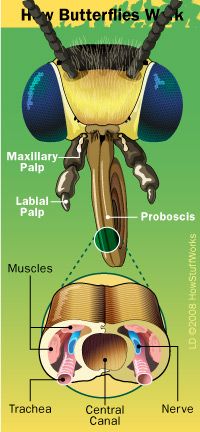

In this article, we'll look at the lives of butterflies from the moment they leave their chrysalis and slowly dry their wings. We'll start with a look at butterfly anatomy, including how they find food through their feet and why their wings are really clear, not colorful. We'll also take a look at some of the surprising food sources for butterflies and whether these fluttering insects may be on their way to extinction.

Advertisement