Before it even emerges from its egg, the very first thing a caterpillar does is eat. It chews its way out of its egg, and then it typically eats the rest of the eggshell. After that, it starts devouring the plant it's standing on. The caterpillar eats until it's literally too big for its body, and then it molts, revealing a newer, roomier skin. Some caterpillars will even eat things that could harm them -- for example, the corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea), a moth caterpillar, uses an enzyme in its saliva to break down the nicotine in tobacco plants that would otherwise kill it.

Insect Image Gallery

Advertisement

It's hard to imagine that a chubby, voracious munching machine will eventually become a delicate, winged butterfly or moth. If you hold a caterpillar and butterfly of the same species next to each other, you might not see any similarities at all. It can seem like the only thing they have in common is single-mindedness: Caterpillars are all about eating, and butterflies are all about sex.

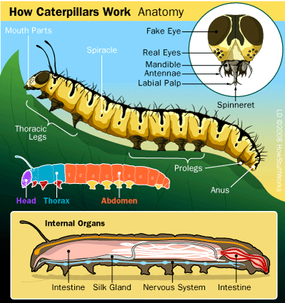

This single-purpose lifestyle is why caterpillars and butterflies look so unlike each other. Their bodies have the same basic parts, including a head, a thorax and an abdomen, but these parts look different because they're suited for very different purposes. A caterpillar's body is adapted for eating food, turning it into fuel and storing it. A butterfly's -- or a moth's -- body is adapted for finding a mate and reproducing.

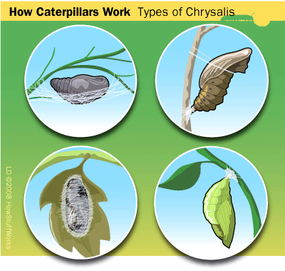

In this article, you'll learn about a caterpillar's journey from egg to chrysalis, and you'll find out exactly what's happening inside the chrysalis as a caterpillar transforms its body into a butterfly. You'll also learn why some caterpillars use their waste as projectiles, eat their own skin or disguise themselves as bird droppings. And if hungry, tent-building caterpillars have commandeered the trees in your backyard, we'll tell you what to do to save your foliage.