Wasp Anatomy and Diet

There are more than 20,000 species of wasps crawling and flying all over the Earth, so it comes as no surprise that a great deal of variety exists when it comes to their color, size, shape and lifestyle. However, a few fundamentals can be found pretty much anywhere you look.

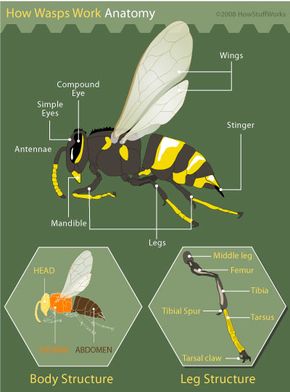

Like all insects, wasps possess hard exoskeletons of chitin, divvied into three body segments:

Advertisement

- The head boasts one pair of sensory antennae, mouthparts for biting and licking, and two kidney-shaped clusters of compound eyes and simple eyes (known as ocelli). Inside the head, a tiny brain tends to the tasks at hand. Some areas of the brain expand when certain species of wasp are confronted with difficult tasks [source: University of Washington].

- The thorax features six spindly legs and a pair of swift, membranous wings. The legs and wings in many species provide enough strength for the wasp to fly away with a paralyzed victim in its grips.

- The abdomen contains the majority of the wasps' organ systems and, in female wasps, a deadly stinger for self-defense and hunting.

Together, these segments create quite the little killing machine. But to understand how this body serves modern breeds of wasps, you have to imagine how it originally served them in the days before flowers.

About 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, Earth was quite a different planet. It was devoid of flowering plants and occupied mostly by conifers, which depend on the wind to spread their seeds. This evergreen world crawled with insects, among which could be found ants and their winged cousins the wasps (both members of the order Hymenoptera). Everyone was fighting for food and survival.

The wasps of this age were carnivorous, preying on spiders and other insects -- many of which in turn fed on vegetation. Plant evolution eventually began to make the most of this constant insect traffic, using it like the wind to carry genetic material from plant to plant. The result was the rise of angiosperms, plants that depend on insects to spread genetic material in pollen from male plant parts, called anthers, to female plant parts, called stigmas.

Basically, these plants learned to trick insects into carrying their genetic material for them. The addition of delicious nectar and pollen only sweetened the deal for the insects, giving them specific reasons to traffic the parts of the plant where pollen was produced. Prehistoric wasps picked up on this free meal and, over time, grew largely to depend on nectar as their primary food source.

As they evolved, honeybees learned to gather pollen and bring it back for their young, but wasps never caught on to the whole honey-and-wax enterprise. So while adult wasps largely put aside their flesh-eating ways to dine out at the local flowering angiosperm, they had to continue bringing meat back for the hungry larvae at the nest -- kind of like vegan parents who bring home a pepperoni pizza for the kids.

This arrangement plays a major role in the life of most species of wasp and is one of the reasons these nectar-eating creatures pack such a powerful sting.