Wasp Stingers

Wasps are known for their stings -- if you know nothing else about them, you probably recognize which end of them to avoid. But where did they get their stingers, and what purpose do they serve?

Step back even further in time to the Jurassic Period, before bees and wasps split ways on their evolutionary paths, and you'd find that those stings can be traced to a little female egg-laying organ called an ovipositor. This is why you'll find only female wasps packing heat.

Advertisement

Prehistoric parasitic wasps would use the pointy appendage to lay eggs directly onto living insects such as caterpillars -- which the hatching larvae would then consume. But why lay your eggs on a caterpillar when, with a little evolution, you can lay them directly inside your victim? So ovipositors grew sharp, sometimes saw-toothed, all to help wasps better perform this surgery. And since the chosen insect hosts tended to take offense and fight off the wasps' advances, the ovipositors also evolved to pack a venomous punch.

Some modern parasitic wasps continue this very practice, either peppering the outsides or filling the bodies of their hosts with dozens of eggs. Other wasps evolved away from the practice, but the venomous stinger remains -- no longer an instrument of reproduction, but a potent biological weapon.

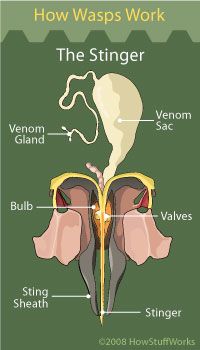

Wasp venom is produced inside a venom gland, then stored in a venom sack. From here, it seeps out through valves to coat a smooth, barbless stinger. The wasp keeps this wicked little weapon stored inside a sheath, ready to plunge it into prey or aggressors at a moment's notice. The males don't have stingers, but this doesn't stop them from bluffing. When cornered, male wasps have been known to brandish their harmless behinds in an empty threat.

But how does wasp venom work, and how can something so small hurt so much? Read the next page to find out.