Have you ever watched a guy with a big, bushy mustache eat? No offense to men with mustaches, but sometimes food gets stuck in there. Imagine what would happen if the guy didn't have any teeth, and that mustache was on the inside of his mouth. Instead of a gross liability when it came to dining, that mustache would be a useful asset when it came to trapping food.

It's a pretty big stretch to imagine a man with a mustache for teeth, but it shouldn't be a stretch to imagine a whale with a mustache for teeth because that very combination exists in nature. Instead of pearly whites, baleen whales have plates with coarse broomlike bristles. Whales are divided into two groups: the odontoceti, which have teeth, and the mysticeti, or baleen whales. In Greek, mysteceti means "mustachioed whale," while, as you might guess, odontoceti means "whale with teeth."

Advertisement

There are a few other differences between the baleen whales and the toothed whales:

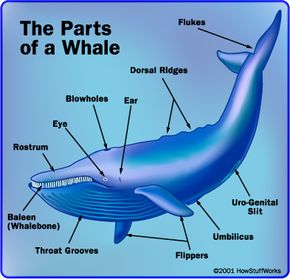

- Baleen whales have two openings in the blowhole, while odontoceti have just one.

- Baleens move more slowly.

- They generally have a smaller dorsal fin (if they have one at all).

- The mustachioed whales are larger than the toothed whales.

But the really important difference comes down to how and what they eat.

While toothed whales are predators that hunt for squid, seals, sea lions and, sometimes, other whales, baleen whales engage in filter feeding, which is a method of consuming many small pieces of prey at once. These whales might eat krill, which are tiny crustacean-like organisms, schools of small fish or plankton. They filter these items out of the water with their specialized feeding plates, known as baleen.

It may sound like a wimpy diet for something as big as a whale, but with each mouthful of water, these whales can filter out thousands of prey items, sometimes taking in 4 tons of food each day [source: Marine Mammal Center].

Toothed whales include the killer, sperm and beluga whales, as well as all dolphins and porpoises. So which whales have these hairy mouths? Find out on the next page.

Advertisement