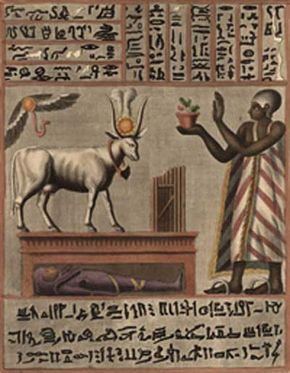

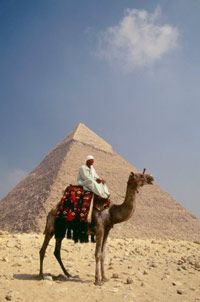

In today's world, we take animal domestication for granted. But from meat and dairy products to faithful companionship, domesticated animals have provided us innumerable products, services and hours of labor that have had profound effect on the history of humanity.

At first, humans used animals merely for food. But eventually, we began to catch on that animals can be useful for work, clothes, protection and transportation. In the wild, animals are protective of themselves and suspicious of other animals. But humans have been able to change this behavior. Over time, some animals become gentler and submit to human instruction -- what's called domestication. In this process, an entire animal species evolves to become naturally accustomed to living among and interacting with humans.

Advertisement

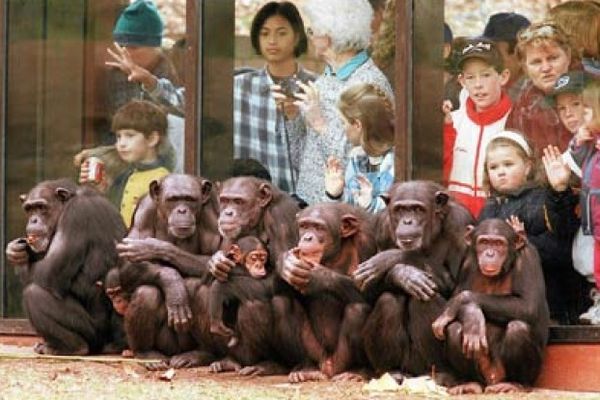

It's important to keep in mind that not everyone believes animal domestication is a good thing. The cofounder of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), Ingrid Newkirk, has famously voiced her opposition to human interference in animal lives. This also means that she dislikes the idea of pets in general. And as an "animal abolitionist," she seeks freedom for all captive animals [source: Lowry].

However, others look on the history of animal domestication in a kinder light. The author Stephen Budiansky argues that it is a perfectly natural process that provides advantages to both humans and animals. Budiansky subscribes to the theory that animals actually chose domestication, preferring the reliable comfort of captivity to the harsh wild [source: Budiansky]. He also points out that there are some species that we have, or could have, saved from extinction by domesticating them.

Regardless, no one can deny the enormous contributions that animal domestication has made to the advancement of humankind. Each domesticated species has offered its own spoils and has its own story of domestication, but all domestication happens through roughly the same biological process. Let's take a look at this process. How do humans orchestrate an entire species' transformation from wild to mild?

Advertisement