Key Takeaways

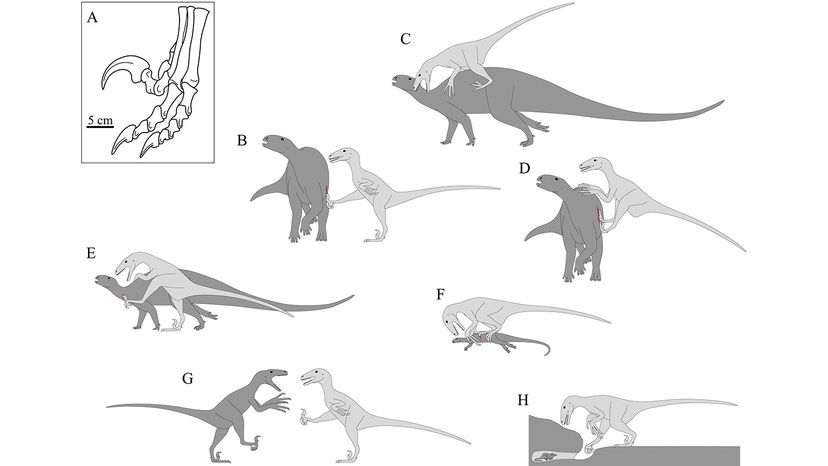

- Deinonychus, a small but fierce dinosaur, lived during the early Cretaceous Period and was known for its agility and sharp, curved toe claws.

- Its discovery in the 1960s changed scientific perceptions of dinosaurs, portraying them as active, dynamic creatures rather than slow, lethargic reptiles.

- The Deinonychus is often credited as the inspiration for the "raptors" in the "Jurassic Park" movies, highlighting its significant role in popular culture.

By the 2010s, it was a well-established art trope. Tenontosaurus was a 20-foot (6-meter) herbivorous dinosaur that roamed North America 115 to 108 million years ago — early in the Cretaceous Period, a chapter in Earth's geological history. It had a beak, a long tail and something of an image problem.

Search for Tenontosaurus artwork on Google and a pattern emerges. In painting after painting, sketch after sketch, we see the poor beast getting ripped apart by a mob of carnivores.

Advertisement

And not just any carnivores. The attackers in these pictures are almost always Deinonychus, sickle-clawed predators who inspired the "raptors" of "Jurassic Park." They may be long-extinct, but in the turbulent 1960s, Deinonychus stood on the front lines of a scientific revolution.

Advertisement