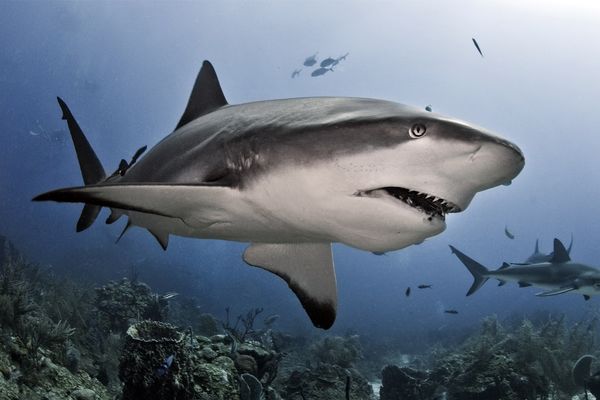

Sharks have a pretty lousy reputation with us humans. But even though looking into the face of an animal with dead-looking eyes and so many teeth sets off all our brain's various "NOPE" alarms, there are more people bitten each year by other humans in New York City alone than by sharks worldwide. The truth is, we might not like sharks, but we actually know very little about them — partly because we've only given them rigorous scientific attention since the mid-1900s. Also, sharks are extremely difficult to keep and study in captivity. Much of what we know about shark behavior, researchers have had to observe in the wild.

Case in point: a new paper published in Science made headlines recently by suggesting the Greenland shark(Somniosus microcephalus) might live 400 years or more, almost doubling the life expectancy of the bowhead whale (211 years), which previously held the title of longest-lived vertebrate known to science. The Greenland shark even approached the record set by Ming the 507-year-old clam, the longest-lived animal ever found.

Advertisement

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen's Department of Biology suspected the Greenland shark's longevity might be off the charts because although it can reach 16 feet (5 meters) in length, the shark grows incredibly slowly, packing on less than a centimeter each year as it drifts around the frigid waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans, gobbling up sleeping seals. To ballpark sharks' ages, the research team collected the bodies of 28 Greenland sharks of varying maturity killed by scientific surveys between 2010 and 2013. Through carbon-14 dating tissue in the center of the lenses of their eyes, they estimated the amount of radiocarbon the sharks were born with. According to the authors, the oldest was probably old enough to have swum underneath the Mayflower as it crossed the Atlantic back in 1620.

This paper's results have raised eyebrows among marine biologists — it sounds outrageous, right? — but the truth is, what we know about sharks is just the tip of the shark iceberg.

What do we still want to know about sharks? Here's a partial list of questions researchers still have about sharks:

- Where do sharks go? "It's hard to track them to get this information," says Dr. Gene Helfman of the University of Georgia's Odum School of Ecology and co-author of Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide. "Technology for putting transmitters on sharks has improved by leaps and bounds in the past decade, and they're finding out almost all of the large sharks move hundreds or even thousands of miles a year — across oceans, up and down entire continents. We're just beginning to understand where they're going and what they're doing." Why sharks migrate and how they navigate are a couple other unsolved shark mysteries.

- How many shark species are there, anyway? Nobody knows, but we have identified around 500 of them. New shark species are being discovered each year — some the size of forks, others the size of buses.

- How and where do sharks reproduce? We know that shark sex is probably pretty rough because female sharks often have scars on their backs and pectoral fins from mating encounters (females also have very thick skin -- just a little thicker than the length of a male shark's tooth), but very little actual shark coitus has ever been observed for many shark species. Where and exactly how most of them do it remains unknown.

- Do sharks sleep? There has been a decades-long dispute raging between researchers over whether sharks sleep, because how would they since most species must keep moving 24 hours a day in order to keep water passing over their gills? It's made researchers ask themselves questions like, "What even is sleep?"

- What part do sharks play in an ecosystem? Some sharks are top predators, obviously, but a shark the size of a banana obviously doesn't fill that role. So what are those guys up to, and what happens when they disappear from an ecosystem?

- Are sharks social animals? Sharks can certainly be found in schools, but nobody knows whether they actively get together to hang out, or whether they just tolerate each other in order to take advantage of a food source or ideal water temperatures, etc.

So, next time you meet a shark, consider: she might have swum underneath the first Europeans to set up permanent camp in North America, and has perhaps never gotten a night of sleep in her life. But we don't know that for sure.

Advertisement