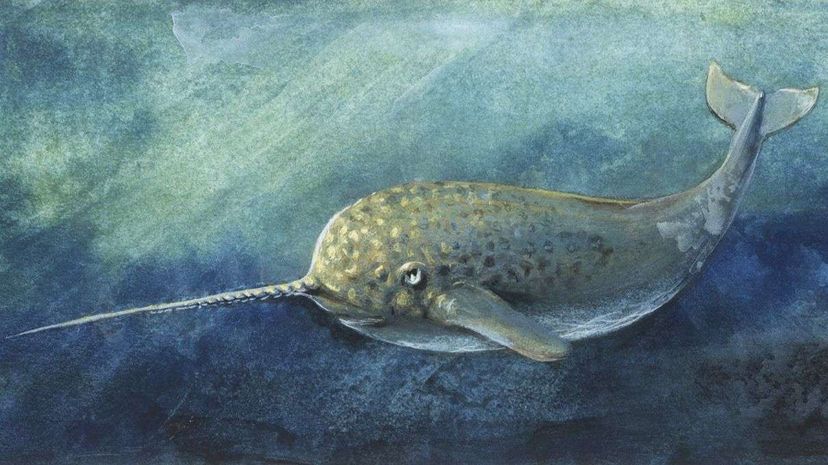

Take a second to think about a narwhal. It's a whale with a unicorn horn — a fairytale animal, right? This article could make all sorts of outrageous claims about narwhals, and you'd probably be like, "OK, I totally buy that."

So it may come as no surprise that this improbable animal of the north seas has superpowers. For instance, the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) uses its spiraled horn, which is actually a modified tooth that can grow to lengths of up to 9 feet (2.7 meters), for a variety of purposes, like testing the chemical concentrations in seawater. The males use their tusks to advertise the size of their testicles to females, and it would be a shame if they didn't fight using them like fencing foils, which — don't worry — they do. But a new study in the journal PLOS One finds the narwhal in possession of the most powerful directional sonar of any animal on Earth. Because, of course.

Advertisement

Lots of marine mammals use echolocation to find their way around in the ocean's murky depths, but this ability to use sound to determine where objects are in space is especially crucial for narwhals. They're deep divers, and one of just two species of toothed whales who live year round in Arctic Circle waters off the coast of Canada and Greenland. The seas are most often completely covered in ice, and narwhals live in complete darkness for much of the year. Since a narwhal has to come up to the surface of the water for air every five minutes or so, they have to be able to precisely and quickly detect small holes and cracks in the ice through which to grab quick gulps of air.

"You don't see open water for miles and miles and suddenly there's a small crack, and you'll see narwhals in it," Dr. Kristin Laidre, an ecologist at the University of Washington, told the New York Times. "I've always wondered how do these animals navigate under that, and how do they find these small openings to breathe?"

To find out, Laidre and her research team placed microphones under the water around ice packs in Baffin Bay. That's off the southern coast of Greenland, and happens to be where 80 percent of the world's narwhals spend their winter. Laidre and her team then listened for the telltale sound of echolocating clicks. They discovered that not only do narwhals produce them at a rate of up to 1,000 clicks per second, and receive the echos back on pads in their lower jaws, they can also direct them with incredible accuracy, like the narrow beam of an adjustable flashlight.

"The data collected in a most challenging environment show that the narwhal emits echolocation clicks with the most directional beam of all echolocators," Jens Koblitz, one of the researchers and study authors, said in a press release.

Other whales broadcast their echolocating sounds in all directions, which is useful for receiving data back from great distances, and it turns out narwhals can do that, too. Other animals like bats and dolphins use echolocation, but the narwhal's ability to focus its clicks bests them all. When narwhals track prey, the study shows, they can widen the sonar beam to take in a larger area. In this way, they can get a sense of their surroundings with more accuracy than any echolocating animal on the planet.

Let this be a lesson to us all, then — just because an animal seems mythologically amazing, that doesn't mean it isn't.

Advertisement