If chiggers thrive where you live, your family lore is probably full of rules for how to avoid the tiny, biting bugs. Be careful where you sit -- stay off the ground, rock walls, decaying wood benches and fallen logs, especially if you're wearing shorts. Also, be careful where you walk. Stay out of tall weeds and patches of brambles, and never pick wild berries without wearing long sleeves and gloves. You may have even heard warnings about specific hiking trails, parts of the yard or patches of vegetation. Venturing into them will leave you covered in chigger bites, but you'll be unharmed if you steer clear.

Arachnid Image Gallery

If you've been unlucky enough to experience chigger bites, you've probably heard a long list of home remedies for them. Friends and relatives might suggest everything from covering the bites in clear nail polish to slathering yourself in turpentine. Unfortunately, few of these remedies actually work, and some of them, like bathing in solvents, are dangerous.

Advertisement

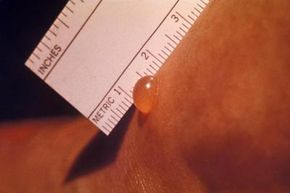

But all the worrying about avoiding chigger bites and the desperate attempts to cure them are understandable. Chigger bites itch intensely, and they can take weeks to go away. Since chiggers go for the thinnest skin on our bodies, the bites tend to cluster in places that are already delicate and sensitive. On top of that, it's rare to get just one chigger bite -- chiggers seem to travel in groups.

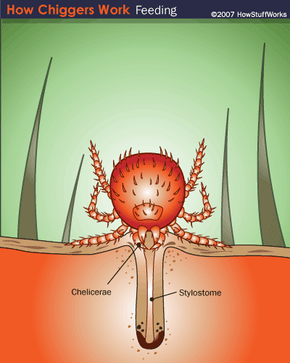

The bites often have a red or white spot in the center. Along with the long-lasting discomfort, these spots often lead people to believe that chiggers are physically imbedded in their skin. This idea that chiggers burrow into people's skin may be the most common misperception about them.

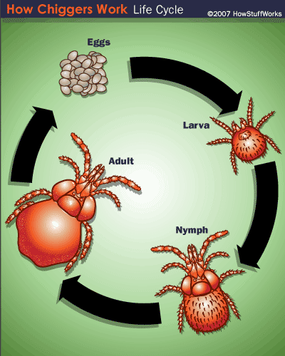

In this article, we'll look at exactly what chiggers are, how they feed and why they cause so much aggravation and discomfort in their human victims. We'll also explore how to find out if there are chiggers in your lawn and how to keep from being bitten.