For evidence of some zoo cons, you need look no further than Maggie the elephant. Until the Alaska Zoo finally caved in to public pressure in 2007, Maggie was forced to spend days on end in a small indoor enclosure because of the frigid outside temperatures. Perhaps as a form of protest, she refused to use the elephant-sized treadmill the zoo brought in to encourage her to exercise [source: National Geographic].

Even in optimal conditions, some experts contend, it's incredibly difficult to provide for the needs of animals like elephants. If Maggie and her captive compatriots lived in the wild, they would wander as much as 30 miles (48 kilometers) a day in large groups, grazing on leaves and stopping to splash in the occasional watering hole. As it is, they're lucky to get a few acres and a roommate or two [source: Lemonick].

Maggie's story is just one of many. Zebras at the National Zoo in Washington D.C. starved to death because of insufficient or incorrect food, and the same zoo's red pandas died after ingesting rat poison [source: Farinato]. And while many zoos, like those in the United States, are supposed to at least meet the minimum requirements spelled out in documents like the Animal Welfare Act, standards aren't always adequate or enforced [source: Farinato].

While conditions have improved from the years of bars and cages, detractors take issue with other items. Although the natural-looking habitats are certainly more attractive, people like David Hancocks, a zoo consultant and former zoo director, describe them as mere illusions, arguing that they're not much of an improvement in terms of space [source: Lemonick]. Indeed, many captive animals exhibit signs of severe distress: People have witnessed elephants bobbing their heads, bears pacing back and forth and wild cats obsessively grooming themselves [source: Lemonick, Fordahl].

Animal behaviorists maintain that their distress is understandable. Animals like zebras, giraffes and gazelles were designed to run across miles of open terrain, not live out their lives in captivity. Despite a zoo's best efforts, its animals often are deprived of privacy, confined to inadequate spaces and unable to engage in natural hunting and mating activities. Forced to live in artificial constructs, many animals succumb to what some people refer to as zoochosis, the display of obsessive, repetitive behaviors [source: Naturewatch].

In addition, many animals have precise needs that zookeepers are just beginning to understand. Some, like the aardvark, survive on a limited diet that zoos have a hard time fulfilling; others thrive only in certain temperatures and environments that aren't easy to recreate.

Even zoos' conservation efforts leave something to be desired. Of 145 reintroduction programs carried out by zoos in the last century, only 16 truly succeeded in restoring populations to the wild [source: Fravel]. The condors mentioned on the previous page? About two-thirds of them were actually strong enough to survive in the wild [source: Encarta].

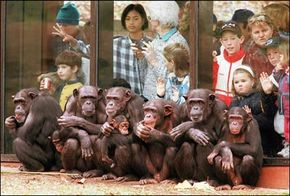

Zoos may not even benefit people as much as once thought. According to one study, many visitors don't pay much attention to the animals -- they're actually talking to each other about unrelated things and spending only a few minutes at each display [source: Booth].

It's a toss-up whether zoos are good or bad for animals. As you've seen, it depends a lot on what zoo you're talking about. It also depends on whether you're referring to the well-being of a single animal actually living in a zoo or an animal, thousands of miles away, benefiting from the zoo's research and conservation efforts. If you had the communicative power of Dr. Doolittle, Leo leopard would likely tell you that zoos are great; however Maggie the elephant might respond by slapping you with her trunk.